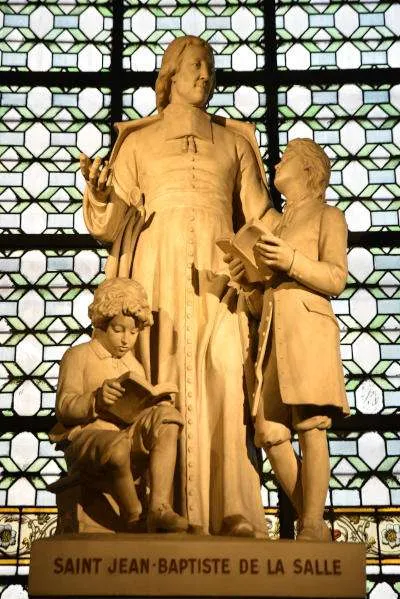

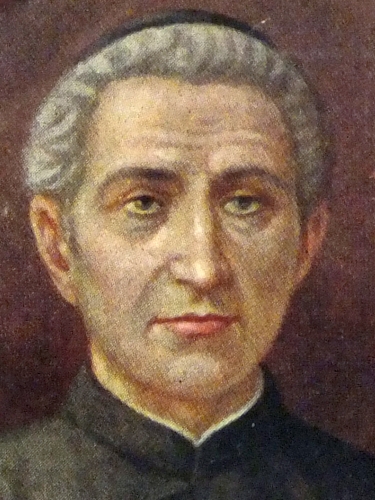

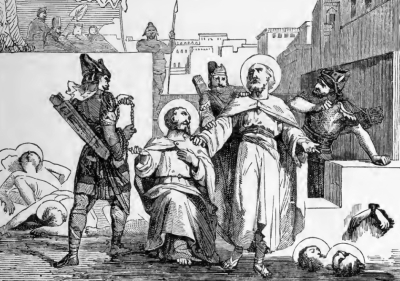

Saint John Baptist de La Salle, Priest

1651–1719; Patron Saint of educators; Canonized by Pope Leo XIII on May 24, 1900

Saint John Baptist de La Salle died on Good Friday, perhaps as a divine sign of the sacrificial life he had lived for the salvation of souls. This wasn’t his first death. His first death was of the life he had lived and the renunciation of the world for the sake of the unexpected mission God gave him.

The Reims Cathedral in France was founded in the fifth century. The first Frankish king to be baptized was baptized there by Saint Remigius, leading to the baptism of many others and the Christianization of the kingdom. After that time, the cathedral became the place where most French kings were crowned throughout the centuries. In its thirteenth-century reconstruction, the Reims Cathedral became one of the most ornate and beautiful Gothic cathedrals in France.

Today’s saint was born into an upper-class family in Reims, and from his youth enjoyed a life of honor and social prestige, as well as an excellent and expensive education. His parents were very devout. When John was eleven, he received tonsure, and he and his parents made a promise of his lifelong service to the Church. At the age of sixteen, he became a canon of the Reims Cathedral. Canons acted as caretakers of the cathedral and advisors to the archbishop. John was then sent to complete his education at some of the finest schools in France. Shortly after beginning his studies of theology at age twenty-one, his parents both died, and he had to return home to care for his six younger siblings and to oversee the family estate. Over the next five years, he completed his theological studies and was ordained a priest at the age of twenty-six. After ordination, he completed his doctorate of theology and immersed himself in the life of a young and well-respected priest.

Father de La Salle’s spiritual director, Father Nicolas Roland, was a saintly man who had a heart for the poor and the education of children. He helped found a new religious order called the Sisters of the Child Jesus whose mission was to care for the sick and educate poor girls. Father de La Salle became their chaplain and confessor and assisted them with their work. When Father Roland was dying, he exhorted Father de La Salle to continue the work of educating the poor youth. Father de La Salle reluctantly agreed, not realizing what he was getting himself into. Soon after, Father de La Salle came in contact with a layman, Adrian Nyel, whom he assisted to found a school for poor boys in Reims, followed by a second one.

Father de La Salle found himself in a dilemma. Naturally speaking, he did not feel drawn to the work of establishing schools for the poor, but he found it difficult to resist the sisters and Adrian who were so passionate about this work, and divine inspiration tugged on his heart. He tried to withdraw but later continued to assist them. Little did he know that he had just begun what would become his life’s work—and a transforming legacy within the Church.

As time went on, Father de La Salle saw a need to better educate the teachers. He himself had received such an excellent education that he was well aware of the teachers’ lack of skills and their poor personal formation. The children that these men were teaching were often very poorly brought up and were “far from salvation,” he would later recount. In response, Father de La Salle began inviting the teachers into his own home, sharing meals with them, and teaching them how to be better teachers and men of God. Eventually, he invited them to live with him in his family home so that he could devote even more time to them. This didn’t sit well with some of his proud relatives who disdained the idea of him so closely associating himself with the lower social class.

Father de La Salle began to experience resistance and criticism. His social peers accused him of trying to make a name for himself as a founder. Some said he was ambitious. They wondered why he was not interested in maintaining the family’s good name, by associating with the peasants. What about his canonry? Would he abandon that prestigious position in favor of educating poor boys and working with simple and poorly educated teachers? Even the bishop raised similar concerns. These criticisms weighed heavily on Father de La Salle, but he prayerfully continued to follow divine inspiration. He resigned as a canon of the cathedral and devoted himself to the full-time work of the education of the poor.

When his parents had died, Father de La Salle had inherited a small fortune. Though he considered using that money to found new schools, he decided instead to give it to the poor who were suffering from a famine in another city, and to rely completely on divine providence for the establishment of more schools. Soon after, he founded the Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools. The brothers lived in common but did not pursue ordination to the priesthood. Instead, they devoted themselves exclusively to the education of poor young boys.

To better assist the brothers, Father de La Salle began to write and organize so as to form the brothers in the art of education. He developed a clear system and classroom structure which was new, ordered, and effective. Teaching poor boys from poorly formed families was challenging. The teachers had to become true masters of teaching, not only of academics but also of forming the boys in virtue and ordered living. Father de La Salle believed that every poor child should be educated for free. He also believed that the youth should learn to read and study in French rather than in Latin. This was a new approach to education. Though he faced much resistance within and outside of the Church, he pressed on. He opened schools for teachers, and his methods and institute grew rapidly.

Father de La Salle remarked later in life that if he had known what God would ask of him from the beginning, he would have never said “Yes.” But God, in His perfect wisdom, led him one step at a time, and Father de La Salle only had to respond to one gentle prompting of grace at a time. Ponder the way God wants to work with you in the same way. He will most likely not reveal His entire plan for your life all at once. Instead, He will lead you and guide you today, giving you the grace you need to respond to His unfolding plan each moment. Say “Yes” today, tomorrow, and every day thereafter, and at the end of your life you will be amazed at how far God has brought you.

Source: http://mycatholic.life/saints/saints-of-the-liturgical-year/april-7-saint-john-baptist-de-la-salle-priest/

Saint John Baptist de La Salle, Priest Read More »