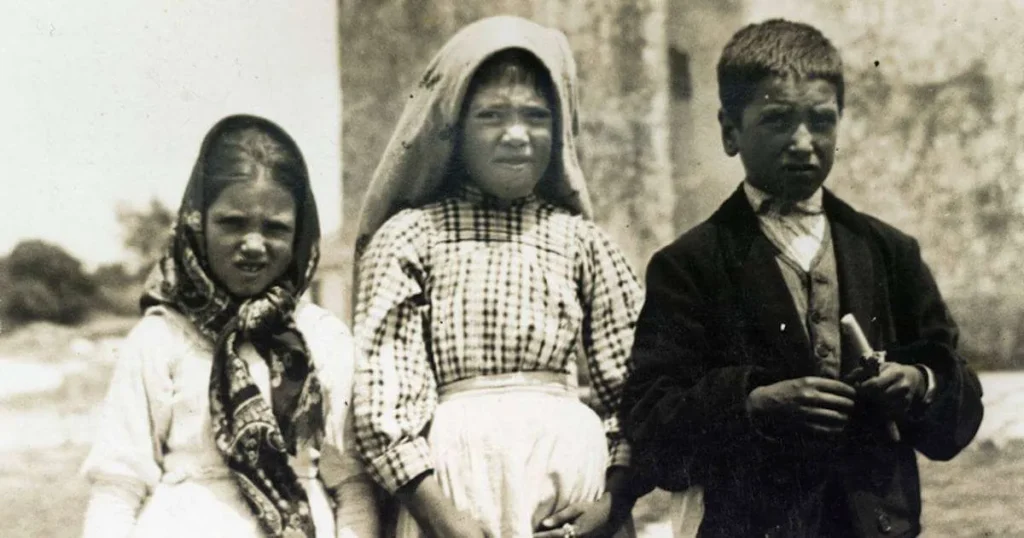

Three Portuguese shepherd children named Lúcia (age nine), Francesco (age eight), and Jacinta (age six), received three apparitions from the Guardian Angel of Portugal in 1916 and six apparitions from Our Lady of the Rosary in 1917. Lúcia later became a religious sister and received several more apparitions from Our Lady and Jesus Himself. These apparitions and their messages are among the most inspiring spiritual events to occur in modern times.

The first apparition took place in the spring of 1916 while the children were tending their sheep. While taking refuge in a cave during a storm, the children had eaten their lunches and prayed the rosary. They were playing games when they saw an angel in the form of a young boy on a cloud, who was whiter than snow, yet transparent and radiant with the sun. The angel said, “Do not fear! I am the Angel of Peace. Pray with me.” With that, the angel bowed to the ground with the children and prayed three times: “My God, I believe in Thee, I adore Thee, I hope in Thee, and I love Thee. I ask pardon for all those who do not believe in Thee, do not adore Thee, do not hope in Thee, and do not love Thee,” and then disappeared.

During the summer of 1916 the angel appeared to them again, almost chastising them, saying, “What are you doing? Pray, pray a great deal! The Holy Hearts of Jesus and Mary have designs of mercy on you. Offer unceasingly prayers and sacrifice yourselves to the Most High.” When Lúcia inquired how they were to sacrifice themselves, the angel replied, “Make of everything you can a sacrifice and offer it to God as an act of reparation for the sins by which He is offended, and in supplication for the conversion of sinners…”

During the fall of 1916, the angel appeared again, this time with a chalice and the Blessed Sacrament before which he bowed and prayed, “Most Holy Trinity, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, I adore You profoundly, and I offer You the Most Precious Body, Blood, Soul and Divinity of Jesus Christ, present in the tabernacles of the world, in reparation for the outrages, sacrileges, and indifferences by which He, Himself is offended. And I draw upon the infinite merits of the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus and of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, that You might convert poor sinners.” Afterwards, the three children received Holy Communion from the angel.

On May 13, 1917, the children, once again in the fields, received a visit from a lady from Heaven. She conversed with them and told them to return to that spot on the 13th of every month for six consecutive months. In their conversation she asked, “Are you willing to offer yourselves to God to bear all the sufferings He wants to send you, as an act of reparation for the sins by which He is offended, and for the conversion of sinners?” To which the children replied, “Yes.”

On June 13, 1917, the lady appeared again, this time with about fifty others from the town present. After they all prayed the rosary, the lady appeared to the children as before and conversed with them. In part, she said, “I will take Jacinta and Francisco soon, but you, Lúcia, are to stay here some time longer. Jesus wishes to make use of you in order to make me known and loved. He wishes to establish in the world devotion to my Immaculate Heart. To whoever embraces this devotion, I promise salvation; those souls will be cherished by God, as flowers placed by me to adorn His throne.”

On July 13, 1917, a crowd of about 5,000 accompanied the children. They prayed the rosary, and the lady appeared as before. This time she gave the children a horrifying vision of hell and then spoke about the need for prayer and sacrifice to end World War I. She also warned that a worse war would come if her message was not heeded. She said, “To prevent this, I shall come to ask for the consecration of Russia to my Immaculate Heart, and the Communion of Reparation on the First Saturdays. If my requests are heeded, Russia will be converted and there will be peace; if not, she will spread her errors throughout the world, causing wars and persecutions of the Church.” Then she asked them to add this prayer to each decade of the rosary: “O my Jesus, forgive us our sins, save us from the fires of hell. Lead all souls to Heaven, especially those who are most in need of Thy mercy.”

On August 13, 1917, as many as 20,000 people had gathered, but on that same day the children were arrested, detained in prison for a few days, and interrogated about their visions. The crowd, however, did see a phenomenon in the sky. On August 19, after the children were released, the lady appeared to them once again in the field.

On September 13, 1917, with a crowd of 30,000, the lady appeared and asked the children to continue to pray the rosary. She promised that if they did, the war would end. She then promised “In October, I will perform a miracle so that all may believe.”

On October 13, 1917, about 70,000 people gathered in the pouring rain. This time the lady revealed her name, saying, “I am the Lady of the Rosary.” She asked for a church to be built on that spot and promised that the war would soon end if they kept praying the rosary every day. When she left the children, everyone in the crowd saw the promised miracle. The sky opened, and those gathered were able to look directly at the sun as it glowed and danced. The sun then plummeted to earth, causing panic, but returned to the sky. Suddenly, everything—including the ground and everyone’s clothing—was completely dry.

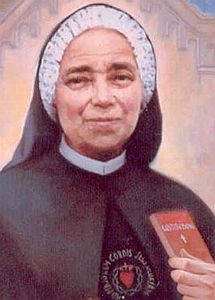

Within a few years, Francesco and Jacinta died and went to Heaven as promised by the Lady of the Rosary. Lúcia entered religious life and received an apparition in 1925 during which Our Lady fulfilled her promise that she would return to ask for “the Communion of Reparation on the First Saturdays.” In 1929, Our Lady appeared to Lúcia again, stating, “The moment has come in which God asks the Holy Father to make, in union with all the bishops of the world, the consecration of Russia to My Immaculate Heart.”

Above all, the messages of Fátima reveal the ongoing need to make reparation for the sins and sacrileges committed against the Sacred and Immaculate Hearts of Jesus and Mary, and to pray for the conversion of poor sinners. Daily sacrifice and penance, offered with prayer and profound faith, do more good than we could ever imagine. As we honor these most glorious apparitions today, reflect upon your own willingness to make reparation for the sins of the world through your daily sacrifices. “Make of everything you can a sacrifice and offer it to God…” Doing so will not only appease the Justice of God, it will also bring about the salvation of many souls.

Source: https://mycatholic.life/saints/saints-of-the-liturgical-year/may-13—our-lady-of-fatima/