The Passion of Saint John the Baptist, Martyr

c. 1 BC–c. 30; Patron Saint of baptism, bird dealers, converts, monastic life, motorways, printers, tailors, lambs, and prisoners; Invoked against epilepsy, convulsions, hailstorms, and spasms; Pre-Congregation canonization

John, the son of Zechariah and Elizabeth, was born approximately six months before the Savior of the World. He was likely born in the small, rural Jewish town of Ein Karem, located in the hill country about five miles west of Jerusalem. The surrounding land would have been utilized for agriculture and herding, centered around a town hub and water well. Uniquely, John was blessed with the presence of both the Son of God and the Mother of God at his birth. Many Catholic theologians, including the Angelic Doctor of the Church, Saint Thomas Aquinas, believe that while John was conceived in Original Sin, he was sanctified in the womb immediately after the Blessed Virgin Mary greeted his mother Elizabeth, several months prior to John’s birth. “When Elizabeth heard Mary’s greeting, the infant leaped in her womb…” (Luke 1:41). This leap in the womb has been interpreted as John’s sanctification by grace before he was born. Jesus would later say of John, “Amen, I say to you, among those born of women there has been none greater than John the Baptist” (Matthew 11:11).

Not much is known about John’s childhood other than what is stated in the Bible, “The child grew and became strong in spirit, and he was in the desert until the day of his manifestation to Israel” (Luke 1:80). Though he would have been raised devoutly in the Jewish faith by his parents in their hometown, John eventually entered the desert, about twenty miles east of his hometown, to live as a hermit, praying, practicing penance, and preparing for his mission.

John’s first mission was to serve as the precursor of the Lord. As the last of the Old Testament prophets and the first of the New Testament prophets, he bridges the gap to Christ. John’s mission was to precede Jesus “in the spirit and power of Elijah to turn the hearts of fathers toward children and the disobedient to the understanding of the righteous, to prepare a people fit for the Lord” (Luke 1:17). Sometime between the years 27–29, John received inspiration from God in the Judean desert and started to gather disciples whom he taught, called to repentance, and baptized with water. John’s preaching was fierce, branding some a “brood of vipers” and demanding evidence of their conversion. He called tax collectors, soldiers, religious leaders, the average townspeople, and even Herod to repent. Many responded.

John’s life reached its earthly climax when he saw Jesus, the Son of God, approaching him in the desert while he was baptizing. John immediately exclaimed, “Behold, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world. He is the one of whom I said, ‘A man is coming after me who ranks ahead of me because he existed before me.’ I did not know him, but the reason why I came baptizing with water was that he might be made known to Israel…Now I have seen and testified that he is the Son of God” (John 1:29–31; 34). John reluctantly baptized Jesus, after which the Holy Spirit descended upon Jesus in a visible form and the Voice of the Father thundered, “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased” (Matthew 3:17). With that, John’s life began to recede into the background, “He must increase; I must decrease” (John 3:30).

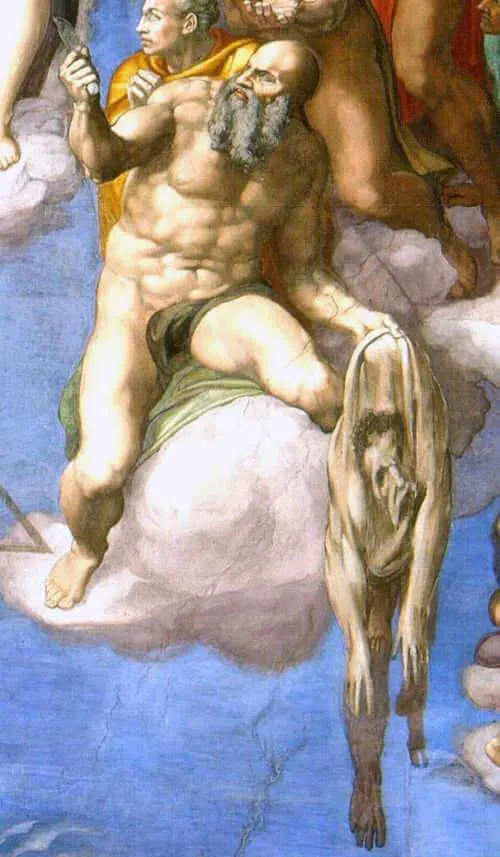

Today, the Church commemorates one of the oldest feasts within the Church, the Memorial of the Beheading of Saint John the Baptist. Just as John preceded Jesus in birth, preaching, and baptizing, so too did he precede Jesus in death, dying as a prefiguration of the one who would give His life sacrificially on the Cross.

John’s death resulted from his bold proclamation of the truth. His call to repentance extended to everyone, including Herod Antipas, the tetrarch, ruler of Galilee and Perea. Although it appears that the area where John was preaching (the Jordan Valley) was not directly governed by Herod, Herod nonetheless was well aware of John’s preaching and his condemnation of him. As a result, Herod was able to have John arrested and imprisoned.

John was most likely imprisoned in a fortress constructed by Herod Antipas’ father, Herod the Great, named Machaerus, northwest of the Dead Sea, in modern-day Jordan. Alternatively, he might have been imprisoned in the Herodium, another palace under Herod’s control just south of Jerusalem.

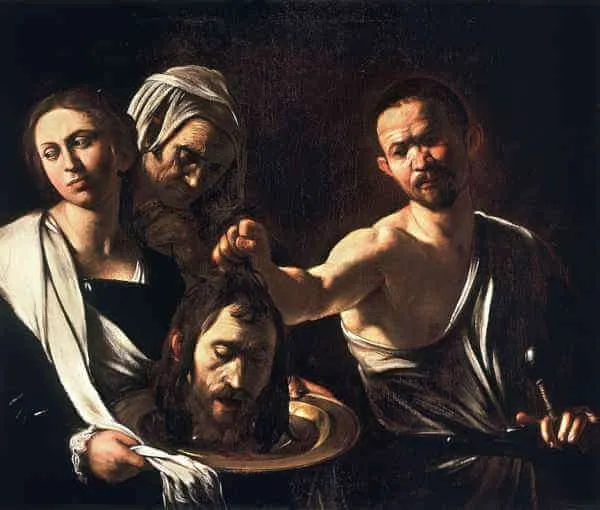

Two of the Gospels narrate the story of John’s death: Matthew 14:1–12 and Mark 6:14–29. John’s criticism of Herod was specific. He condemned Herod’s unlawful marriage to his brother’s wife, Herodias. Though Herod seemed to fear John and his disciples because of John’s popularity and the power of his words, he decided to appease Herodias’ hatred of John for condemning her and Herod. On Herod’s birthday, Herodias’ daughter, traditionally named Salome, performed a dance for Herod and his guests that so pleased him that he promised her anything she asked of him, up to half of his kingdom. Her mother saw her opportunity for revenge and convinced her daughter to ask for the head of John the Baptist on a platter. In his weakness, Herod complied.

After John’s death, the Bible tells us that “His disciples came and took away the corpse and buried him; and they went and told Jesus” (Matthew 14:12). The news caused Jesus to withdraw alone in a boat to a deserted place to pray. Jesus not only grieved with human sorrow over the death of his cousin, but he also came face-to-face with the reality of His own fate. Thus, His time of prayer was a period in which He perfectly renewed His fidelity to the Mission on which He was sent, to give His life for the salvation of souls. Traditionally, it is believed that John’s body was buried in the town of Sebaste, about fifty miles north of Jerusalem. Various traditions have evolved over the centuries about what happened to his head. Some say Herodias buried it in a dung heap to hide it from his followers and it was later discovered, buried in the Mount of Olives, and today is preserved in the Church of San Silvestro in Capite, Rome, Italy. This tradition, among many others, is impossible to confirm.

As we honor this man so highly honored by our Lord, we also honor our Lord Himself. John’s life was given to the mission to which he was called. He never wavered and willingly accepted even death, rather than shy away from God’s will. He introduced the Lamb of God to the world and led the way for Jesus by his preaching, baptism of repentance, and death, which prefigured Jesus’ own death. As you ponder Saint John’s life, reflect especially upon the wholehearted commitment he made to selflessly give himself to the mission he received. Where you see hesitancy in your own life, take inspiration from Saint John the Baptist, praying that you will exemplify his courage and resolve to fulfill the will of God.

Source: https://mycatholic.life/saints/saints-of-the-liturgical-year/august-29the-beheading-of-st-john-the-baptist/

The Passion of Saint John the Baptist, Martyr Read More »