Yesterday, the Church honored Saint Monica, the mother of today’s saint, Saint Augustine. Despite her challenging life, Monica fulfilled her most crucial duty as a mother and wife. She prayed for her family and demonstrated such compelling virtues that her husband, mother-in-law, and all three of her children were converted to Christ. Among them was Saint Augustine of Hippo, one of the Church’s most revered saints.

Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis, known as Augustine, was born in Tagaste, present-day Souk Ahras, Algeria, North Africa. He was the oldest of three children, including a younger brother and sister. His father, Patricius (Patrick) was not wealthy but had civic responsibilities in his city, which was part of the Roman Empire. His father was a pagan, known for his violent temper and immoral lifestyle. Augustine’s mother, known today as Saint Monica, struggled with alcohol at an early age but overcame that vice. She was raised a Christian and wholeheartedly embraced her Catholic faith. Despite suffering due to her husband’s temper and adulterous behavior, Monica was a model of charity, and her prayers eventually converted her whole family.

Augustine’s father would not permit his children to receive baptism, despite their mother’s pleas. Nevertheless, Monica ensured their catechetical formation from an early age, as well as an education in the classics. Monica’s faith instilled within Augustine an awareness of Christ his Savior, but that awareness never fully penetrated his young mind. Instead, he became a troublemaker. For instance, he and his friends once stole some pears, not because they were hungry or because the pears tasted good, but merely for the thrill of it. He later recounted in his Confessions, “I loved my own undoing. I loved my error—not that for which I erred but the error itself…seeking nothing from the shameful deed but shame itself. It was a love of sin.”

Because Augustine excelled in his studies in his hometown, his proud father decided to send him to the thriving nearby city of Carthage to continue his education, once he could find someone to pay for it. This took several months, and Augustine’s idleness during that time only led him into greater mischief. His father died that year, but a wealthy citizen of Tagaste offered to sponsor Augustine’s education. By the time he arrived in Carthage, he was ripe for a life of sin. Many of the other students lived immorally, the theaters stirred up his passions, and he became intoxicated by his literary successes. Shortly after his arrival, he moved in with a young woman and fathered a child out of wedlock. When he was nineteen, he read a book that would begin to change his life: Cicero’s Hortensius. Although that book is now lost to history, it extolled the virtue of wisdom. Reading it awakened a hunger for truth within Augustine, which he began to pursue earnestly. Unfortunately, at this time he started doubting his Christian faith, primarily due to his struggles with the Old Testament, which he perceived as violent and confusing. He then encountered the religious philosophy of Manichaeism, which claimed to have discovered secret knowledge and supported his view that the Bible had contradictions. Manichaeism looked at reality as a struggle between light and dark, good and evil. It regarded the created world as part of the dark side, aiming to trap us in darkness. This new religion influenced him, and he looked into it more. Although he never formally joined, he pursued their teachings in the hope of discovering the wisdom they promised. Several years later, he would abandon them altogether, especially after meeting their leader, Faustis, who proved a disappointment and less than wise.

When Augustine completed his studies in Carthage around the age of nineteen, he returned home to Tagaste with his girlfriend and son and began teaching grammar at a local school. When he told his mother he was considering becoming a Manichaean, she threw him out of her house but later reconciled with him due to divine inspiration she received. He was so successful as a teacher that he was invited back to Carthage a few years later to teach Rhetoric. After several successful years, he received an invitation to Rome, which was a great honor. When he informed his mother, she told him that she was going with him, to which he reluctantly agreed. However, Augustine tricked his mother and left for Rome without her. In Rome, he became disgusted with the students who cheated him out of tuition fees, and after a few years, accepted a position in Milan. It was in Milan, when Augustine was thirty years old, that his mother finally caught up with him and witnessed his conversion.

Still searching for the truth, Augustine met the future saint, Bishop Ambrose of Milan. Ambrose was a great thinker and preacher. He also paid attention to Augustine, listening to him, offering him friendship, and answering his many questions. Ambrose introduced him to the proper reading of the Bible, especially helping him with his difficulties with the Old Testament. When Ambrose came into conflict with the Empress Justina who was trying to take his Cathedral and make it Arian, Ambrose stood his ground in an act of great courage and defiance. She backed off and Augustine was greatly impressed.

One day while sitting in a garden, Augustine heard a child’s voice say to him, “Take and read.” Although he didn’t know where the voice came from, he picked up the Bible next to him and randomly opened to Romans 13:13-14 which read, “…let us conduct ourselves properly as in the day, not in orgies and drunkenness, not in promiscuity and licentiousness, not in rivalry and jealousy. But put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the desires of the flesh.” This passage affected him so deeply that he began his conversion in haste.

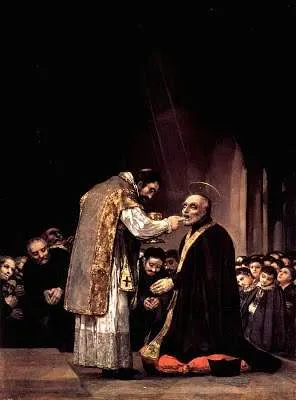

Augustine spent time with good Catholic friends and had lengthy conversations, which helped him immensely. His mother’s presence was also a great support. Although she was uneducated, her wisdom and insight into the truth were undeniable, and she always held her own with her well-educated son. All of this, coupled with Monica’s tearful prayers, led the thirty-two-year-old Augustine toward his final conversion and baptism the following year by Bishop Ambrose during the Easter Vigil in 387, along with his son. Once baptized, Augustine decided to return to his hometown with his mother, son, and friends. On the way, his mother fell ill just outside of Rome and died. Augustine later recounted her passing in the Confessions, which is one of the most beautiful depictions of a mother and son’s love ever written.

Upon returning to Tagaste, Augustine formed a religious community with his friends. His reputation within the Christian community grew quickly, and their hometown genius who had become a Catholic became a source of hope for many. By acclamation of the people, he became a priest in 391 and was consecrated as bishop of the nearby town of Hippo in 396. During his forty-three years as a Christian, Augustine became one of the greatest, if not the greatest, theologians in the history of the Church. His pastoral work with the people, his regular sermons, and his attentiveness to the people’s needs changed their lives.

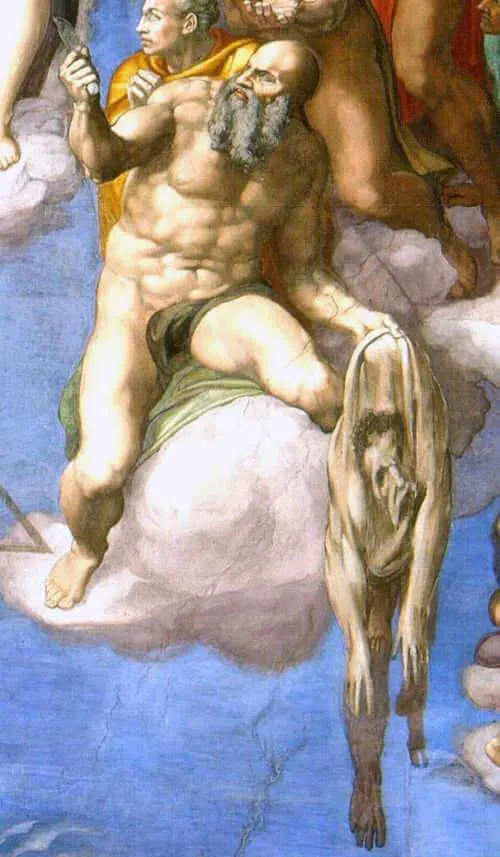

Augustine’s voluminous writings remain among the most read and quoted texts today. His works include apologetics, sermons, letters, scripture commentaries, a monastic rule, and philosophical and theological treatises. His greatest work, Confessions, is autobiographical, deeply personal, and humble. It traces his internal conversion and intersperses it with profound theological insights. In his other great work, City of God, he defends the faith and refutes the idea that the sack of Rome in 410 was caused by a rejection of pagan gods. Instead, he compares the city of man with the city of God, pointing society to the ideals to which it is called. He also wrote a famous work on the Trinity, among numerous other works. In total, over five million words written by Augustine have survived until today, numbering over 1,000 documents. In his last year of life, he witnessed the destruction of Hippo as the barbarians invaded, murdered, destroyed churches and buildings, and overthrew the town as they had done in Rome years earlier. They could not, however, destroy the lasting impact Saint Augustine would have. His influence extends far beyond the Church; he has profoundly impacted the entirety of Western thought.

As we honor this pillar of wisdom, consider especially Augustine’s personal journey towards Christ. In many ways, Saint Augustine lived two lives. At first, he was a weak, confused, and sinful man. After that, he became a sinner who was redeemed and transformed by grace. His struggle led him to the truth and when that happened, God used him in extraordinary ways. His life can be summed up in one of his most famous quotes, “Our hearts were made for You, O Lord, and they are restless until they rest in you.” Ponder your own story of conversion, and especially any ways that you are restless. Follow this saint’s example and seek the Truth with all your heart, knowing that God will reveal Himself to you when you are ready, so that you can rest in Him.

Source: https://mycatholic.life/saints/saints-of-the-liturgical-year/august-28st-augustine-of-hippo/