Once Christianity was legalized in the Roman Empire in the fourth century, many people in Roman-Britain began to convert. However, in the fifth century, after the fall of the Roman Empire, Britain slowly fell to invasion and conquest by the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes from modern-day Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands. These people brought with them the religious practice of Germanic paganism, which held a polytheistic belief in both major and minor gods who were invoked for war, governance, fertility, prosperity, and many other aspects of human life. These Germanic pagans also practiced ancestor and nature worship; engaged in rituals, festivals, and magical spells; and had a strong oral tradition. At the end of the sixth century, Saint Augustine of Canterbury began a missionary expedition that marked the beginning of the re-Christianization of the British Isles.

Less than a century later, today’s saint, Saint Boniface, a descendant of the Germanic pagans who had conquered Roman Britain just a couple of centuries earlier, was born into one of those recently Christianized kingdoms of England. Later in life, Saint Boniface would return to the lands of modern-day Germany and the Netherlands, from which his ancestors came, to convert the pagans, help organize the Church, and unite it more closely with the pope in Rome.

Saint Boniface (named Wynfrid at birth) was born into a noble family in the Kingdom of Wessex in southern England. As a youth, Wynfrid was raised in the Catholic faith and received a good education. When missionary monks visited his hometown, Wynfrid was inspired to follow their example. His father initially disapproved but eventually gave his consent. Wynfrid was first sent to a nearby Benedictine monastery for seven years and then to the Abbey of Nursling, about 100 miles away.

At Nursling, Wynfrid excelled in his studies and prayer life, made vows as a Benedictine monk, and was ordained a priest at the age of thirty. As a young priest, Father Wynfrid quickly became known as an excellent preacher and teacher with a profound understanding of Sacred Scripture, as well as an excellent administrator, organizer, and diplomat.

During the first several years of Father Wynfrid’s priestly ministry, he kept sensing a call to evangelize the people of his ancestral homeland. Though he had no personal connection with the people, he did share their language, or at least a dialect of that same language. In 716, after being a priest for about ten years, Father Wynfrid began to realize his missionary calling by obtaining permission from his abbot to travel north to Frisia, modern-day Netherlands, to assist a missionary priest in that territory. At the time, the local pagan king was at war with the Christian Frankish king, which made missionary activity difficult. The pagans were unlikely to convert to the religion of those they were fighting. Father Wynfrid also observed that the Frankish Church needed reform, organization, and stability if it was going to flourish.

After what could be seen as a failed mission to Frisia, Father Wynfrid returned home to his monastery in Nursling. In the fall of 718, he traveled to Rome to consult with the Holy Father regarding his desire to evangelize the Germanic pagans. Pope Gregory II received him, evaluated his motives, and on May 15, 719, sent him north to evangelize the pagans. The pope also changed Wynfrid’s name to Boniface, which means “doer of good.” Despite expected challenges, within three years there was much good fruit, and the pope called Father Boniface to Rome for an update and new orders.

In Rome, in 722, Pope Gregory II was so pleased with Father Boniface that he ordained him a bishop. The pope named Boniface the regional bishop of all of Germany and sent him back with letters to the Frankish king and the clergy of the various dioceses, instructing them that Bishop Boniface was now in charge. With this new authority, Bishop Boniface went to work to better organize the Frankish Church, build new monasteries and churches, and improve relations between the Catholics and pagans.

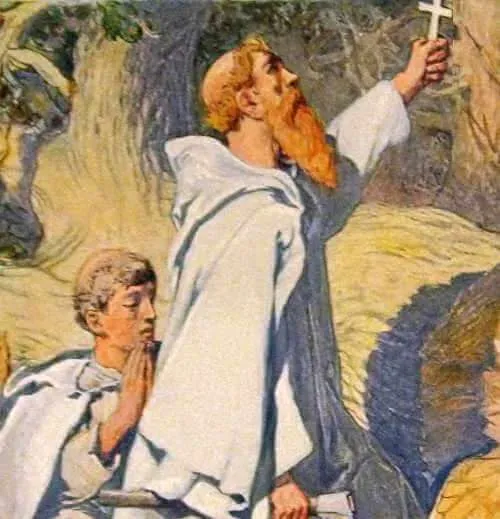

Legend has it that Bishop Boniface won the esteem of many of the pagans one day when he felled a huge oak tree considered sacred by the locals. It is said that after striking the tree with an ax, a powerful wind came and blew it over. The people were so surprised that Thor, the god of thunder, didn’t strike Boniface down that they began to inquire more about the Catholic faith. Bishop Boniface then used the wood of that tree to build a chapel and monastery under the patronage of Saint Peter.

Over the next thirty years, Bishop Boniface was a powerhouse of evangelization, organization, and reform. He built monasteries and churches, called synods in which clear ecclesiastical laws of governance for the Frankish church were established, worked with the Frankish kings and local authorities, served under four popes, and continued to create the foundational framework for the important mission of evangelization of the pagans.

At the age of seventy-nine, after being satisfied with his organization of the various dioceses throughout Germany, Bishop Boniface decided to return to Frisia, where it all had started, to preach and convert the remaining pagans. After much success, while preparing to celebrate the Sacrament of Confirmation for the new converts, Bishop Boniface and dozens of his companions were murdered, most likely by common thieves. When the murderers pillaged through their belongings, they found nothing of value to them, mostly books and letters that they threw in the forest, since they didn’t know how to read. Those books and letters were later found and are preserved, including a Bible believed to have been used as a shield by Bishop Boniface as he was slain by a sword. The bishop and his companions died with courage, not fighting back. The bishop’s last words are recorded as, “Cease, my sons, from fighting, give up warfare, for the witness of Scripture recommends that we do not give an eye for an eye but rather good for evil. Here is the long awaited day, the time of our end has now come; courage in the Lord!”

Saint Boniface is known as the “Apostle of Germany.” Early in his life, he heard God calling him to be a missionary, and he generously responded. As a result, God did powerful things through him for the good of his ancestral home and beyond. His impact was so great that the seeds he planted in Germany greatly contributed to the shaping of modern-day Europe. As you ponder the great fruit born by Saint Boniface’s courage and zeal, prayerfully offer your own life to God, vowing to serve Him and His Church in any way He calls.

Source: https://mycatholic.life/saints/saints-of-the-liturgical-year/june-5—saint-boniface-bishop-and-martyr/