Dedication of the Lateran Basilica

“Destroy this temple and in three days I will raise it up.” The Jews said, “This temple has been under construction for forty-six years, and you will raise it up in three days?” But he was speaking about the temple of his Body. John 2:19–21

Reflection:

The most important temple is the temple of a person’s soul because God dwells within each one of us. In the most secret center of our being is that sacred sanctuary where we meet God. Saint Teresa of Ávila called it the Presence Chamber, the most central and interior dwelling place within us.

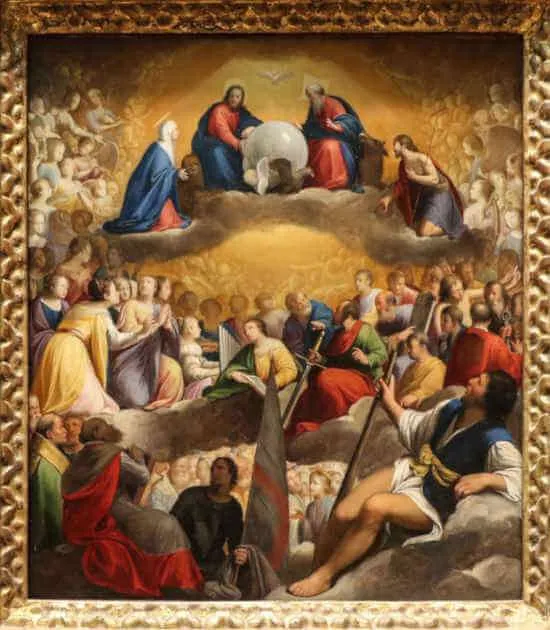

In addition to the temple of the soul, there are many sacred places throughout the world. There are shrines, churches, basilicas, grottos, cathedrals, and other holy places that are set aside for the sole purpose of worship of God. They are to be a Heaven on earth, a place where we join with the Seraphim, Cherubim, and Thrones in their angelic praises of the Most Holy Trinity. Today’s feast commemorates one such place, the most important church on earth.

In the city of Rome, there are four major basilicas. The first three are Saint Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City, the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls, and the Basilica of Saint Mary Major. The fourth is the Archbasilica Cathedral of the Most Holy Savior and of Saints John the Baptist and John the Evangelist in the Lateran, also called Saint John Lateran, or the Lateran Basilica for short. Of the four major basilicas, the oldest and most important is Saint John Lateran, the dedication of which is remembered today. Though the pope now lives next to Saint Peter’s Basilica, Saint John Lateran is the official cathedral of Rome. That means Saint John Lateran is not only the mother church of the Archdiocese of Rome but also the mother church of the entire world.

The church building has a long and storied history. In the year 64, the erratic and cruel Roman Emperor Nero blamed a devastating fire in Rome on the Christians. In retaliation, he ordered the execution of many Christians, including Saints Peter and Paul. In 65, there was a conspiracy to kill Nero with the help of the Counsel-designate Plautius Lateranus (Lateran). When Nero learned of the plot, he immediately beheaded Lateranus and confiscated his home, the Lateran Palace. Subsequent Roman emperors used the palace in various ways over the next 250 years, such as a military fort. In 312, when Constantine the Great became the sole ruler of the Western Roman Empire, he took possession of the Lateran Palace. The following year, after issuing the Edict of Milan with Emperor Licinius of the Eastern Roman Empire, Constantine donated the Lateran Palace to Pope Miltiades who first used it to conduct a synod of bishops and then began constructing the first Basilica in Rome. Upon its completion in the year 324, it was dedicated by Pope Sylvester and given the name the “House of God,” with a special designation to Christ the Savior. With that, the first cathedral in the most important diocese was established.

Constantine the Great did much to help the Catholic Church flourish after legalizing its practice. He saw to it that the Lateran Basilica was beautifully decorated with gold and silver. He also built many other churches in Rome, Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and Constantinople. Up until that time, the church had suffered greatly, always fearing persecution and death. Now, it had its first cathedral in the heart of Rome, beautifully decorated, with the Roman Emperor’s full support.

Though the basilica was first dedicated to Christ the Savior, in the tenth century Pope Sergius III added a new baptistry and rededicated the basilica to Saint John the Baptist. In the twelfth century, Pope Lucius II dedicated the basilica to Saint John the Evangelist. The basilica, therefore, honors Christ the Savior first and the two Saint Johns as the co-patrons.

Though the Lateran Basilica has remained the pope’s cathedral from the time of its dedication, the Lateran Palace, next to the Basilica, was the papal residence from 324–1305. In 1305, Pope Clement V was elected to the papacy and refused to move to Rome. In 1309, he moved the entire papal court to Avignon, France, where it remained until Pope Gregory XI returned to Rome from Avignon in 1377. Upon the pope’s return to Rome, the Lateran Palace was in disrepair due to two fires, so the pope eventually built a new palace next to Saint Peter’s on Vatican Hill, where every subsequent pope has resided until today.

As we honor the mother church of the whole world, ponder the importance of a church building. A church is sacred because it is exclusively dedicated to the worship of God. Saint John Lateran is an exclusive-purpose church. It is the pope’s cathedral from which the entire Church is governed and the central place of worship for the world. As we honor the dedication of that church in 324, pray for the Church today. Pray for your local parish, religious institutions, religious orders, dioceses, national conferences, and the Universal Church headed in Rome. Our churches and sacred places exist to be places where we come to encounter God. Pray for the pope in a particular way today, that Saint John Lateran will always be a place where he, and every pope after him, will encounter God in a profound way.

Source: https://mycatholic.life/saints/saints-of-the-liturgical-year/november-9—feast-of-the-dedication-of-the-lateran-basilica-rome/

Dedication of the Lateran Basilica Read More »