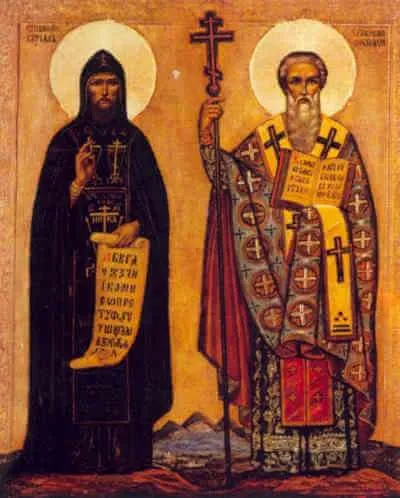

Saint Cyril, Monk; Saint Methodius, Bishop

Saint Cyril: c. 827–869; Saint Methodius: c. 815–885; Co-Patrons of Europe, Slavic peoples, unity of Eastern and Western Churches; Pre-Congregation canonization

Imagine what life would be like if you were unable to read because the language you spoke was not even in written form. No alphabet, no books, only a spoken language. This is the context into which our saints today were sent to preach the Gospel.

Their story began in Thessalonica, Greece, a territory first evangelized by Saint Paul. Seven sons were born to a Greek-speaking imperial magistrate and his wife. Two of the boys were named Constantine and Michael. Their mother was most likely of Slavic descent, and the boys learned her unwritten language, along with Greek and Latin. When Constantine was about fourteen years old, he was sent to the great Greek city of Constantinople to study. It was there that he also came to know the young Byzantine Emperor, Michael III, who was only a young child. After completing his education, Constantine decided to become a priest. Shortly after his ordination, he was invited to teach and soon became well known as the “Philosopher.” Constantine’s brother Michael, about twelve years older than Constantine, began his career in civil service in Macedonia but chose to abandon that position to become a monk, taking the name Methodius.

When Constantine was about thirty years old and his brother Methodius was in his early forties, Constantine decided to give up his teaching career and embrace a life of prayer in his brother’s monastery. Within a few years, however, Emperor Michael III, now an adult, asked Constantine to go on a mission to evangelize the Jews and Turks of Khazars, modern-day Russia, Ukraine, and Crimea. Methodius accompanied him on this mission, and they learned both Hebrew and Turkish so as to speak to the people in their native tongues.

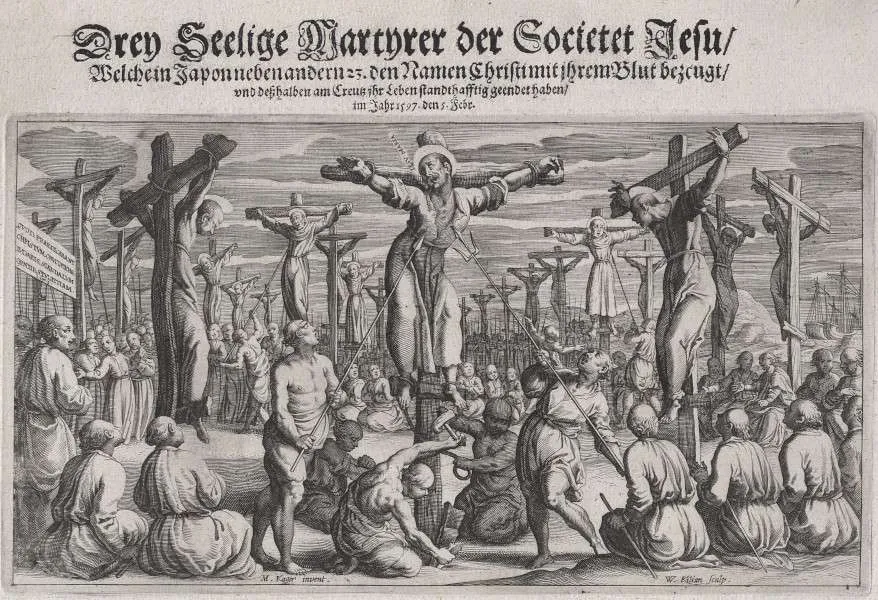

Within a couple of years, Prince Rastislav of Moravia asked Emperor Michael III to send missionaries to Great Moravia, today’s Czech Republic. His people had rejected paganism and embraced Christianity, but they didn’t have anyone who could explain the faith to them in their native Slavic language since the Germanic clergy adhered strictly to Latin. It was this mission that would be the beginning of a new era and a new method of evangelization within the Church.

In Great Moravia, Constantine and Methodius began to translate the Bible and liturgical books into the Slavic language. Since there was no written form of the language or even an alphabet, Cyril created one. He translated the various sounds into symbols, which enabled him and his brother to then write down the sacred texts. In addition to their translations, they began to teach the people and future Slavic clerics how to read their new written language. Eventually, the new alphabet developed into what is now known as the Cyrillic alphabet and is the basis of many Eastern European and Asian languages used by more than 250 million people today.

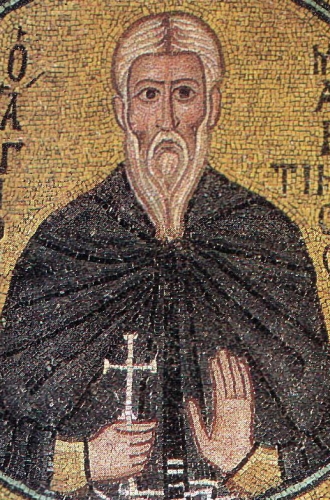

Despite the fact that the Slavic people were overjoyed to hear the Gospel and pray the liturgy in their native language, many of the Germanic clergy took issue with this approach. To solve this problem, the brothers traveled to Rome where they received the approval of Pope Adrian II, who ordained them bishops and sent them back to Great Moravia. Before leaving Rome, however, Constantine fell sick. Before dying, he fully consecrated himself to God as a monk in one of the Greek monasteries, taking the monastic name Cyril. His brother Methodius then returned to Great Moravia to continue his work.

Bishop Methodius spent the next fourteen years evangelizing the people in their native language, forming clergy, and effectively administering the Church. He continued to endure harsh treatment from the Germanic clergy, even being imprisoned by them for a time, but he pressed on, extending his missionary work even beyond the borders of Great Moravia.

It wasn’t until a millennia later that these brothers received the universal honor they deserved when the Western Church added them to its liturgical calendar. A century after that, Pope John Paul II, a Slav himself, honored these two brothers with the title of co-patrons of Europe and Apostles to the Slavs.

These great brothers teach us that the Gospel must be personal and understood through the prism of our own language, culture, and human experience. They also teach us that we must work to share the Gospel with others in ways that they understand and to which they can relate. As we honor these great missionaries, ponder the ways that God wants to use you to reach out to others with His saving message. Though you might not be called to invent a new alphabet to do so, you will be called to step out of your comfort zone. Be courageous, creative, and zealous in this effort in imitation of these Apostles to the Slavs.

Source: https://mycatholic.life/saints/saints-of-the-liturgical-year/february-14-saints-cyril-monk-and-methodius-bishop/

Saint Cyril, Monk; Saint Methodius, Bishop Read More »