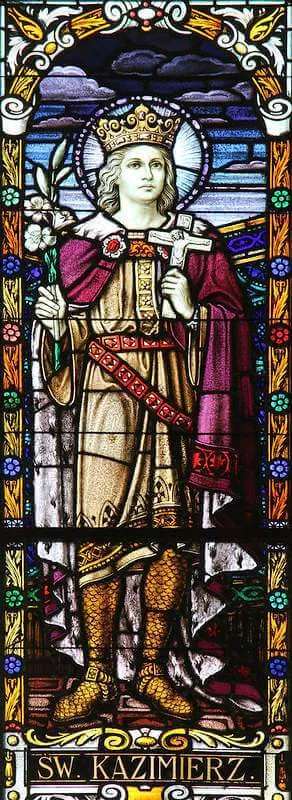

c. 1045–1093; Patron Saint of learning, parents of large families, parents who have lost a child, queens, and widows; Canonized by Pope Innocent IV in 1251

Margaret of Wessex was born into English royalty. Her grandfather was King Edmund the Ironside, who reigned as king for less than a year. After King Edmund’s death, Margaret’s father, Edward, might have been sent to the court of the King of Sweden for protection, and later to Kyiv when he was only an infant. For that reason, he is commonly referred to as Edward the Exile. In 1046, Prince Andrew of Hungary became King of Hungary, and Edward the Exile entered into his service, eventually marrying Agatha and having three children: Margaret, Christina, and Edgar Ætheling. Little is known about Agatha, but one theory is that she was the granddaughter of Saint Stephen, King of Hungary, and the daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Henry II. Agatha and Edward the Exile were good parents to their three children, seeing to it that they were well educated and raised in a strong Catholic home.

In 1042, Edward the Confessor became King of England—and was later canonized, the only English king to become a saint. King Edward the Confessor did not have any heirs to whom he could pass on the crown, so he called Edward the Exile (Margaret’s father) and his family back to England where they entered the royal court. Edward the Exile died soon afterward, making Margaret’s brother, Edgar Ætheling, a potential heir to the throne.

In 1066, when King Edward the Confessor died, conflict arose as to who had the right of succession. During the confusion, the nobles quickly chose Harold II and had him crowned as king. However, a distant relative, William of Normandy (also known as William the Conqueror), made a claim to the throne. William offered many reasons, including a claim that Harold had sworn an oath to him to support him as King of England and had sworn the oath over the relics of a saint, making it binding. Even the pope agreed with William’s claim. Shortly after Harold II was crowned as king, William attacked England, and Harold II was killed in battle. The nobles supported Edgar Ætheling, Margaret’s brother, as the next king, but when William rode into London, the nobility surrendered and Edgar relinquished his claim to the throne, never having been crowned.

In 1068, the widowed Agatha decided to protect her children from the Norman conquerors and from potential chaos that might result from a rebellion against them. She boarded a ship with Edgar, Margaret, and Cristina, and set sail for her home, probably Hungary. Legend has it that the ship was tossed off course and wrecked on the shores of Scotland. In Scotland, King Malcolm III welcomed the exiled royal family and provided for their safety.

Since childhood, Margaret had grown in a profound love of God. She lived a very strict and ordered life, studied the Sacred Scriptures and other pious books, and grew in a keen understanding of the things of God. Her earliest biographer described her as another Mary of Bethany, who sat at the feet of Jesus, listening to His Word and pondering it in her heart.

When this royal family arrived in Scotland, the young King Malcom, a widower with two sons, immediately noticed Margaret’s beauty. Her physical beauty was greatly enhanced by the beauty of her soul, manifested in her piety, virtue, and intelligence. It didn’t take long before the two fell in love and were married, making Margaret Queen of Scotland.

Queen Margaret quickly realized that the power and influence she had received ought not be used for her own selfish purposes but for the betterment of Scotland and, especially, for the increase of the Kingdom of God. As queen, Margaret quickly won the love and admiration of the people. As her first biography stated, “Nothing was firmer than her fidelity, steadier than her favor, or juster than her decisions; nothing was more enduring than her patience, graver than her advice, or more pleasant than her conversation.”

Prior to Margaret’s arrival in Scotland, the Scottish Church followed the old Celtic traditions. When the Romans withdrew from Britain in the fifth century, the Scottish Church became isolated from the Roman Empire and the Church’s development. In Scotland, abbots of monasteries provided the main source of Church influence and governance, rather than bishops of dioceses. Liturgical practices differed, including the liturgical calendar and customs.

Queen Margaret had been raised within the Roman tradition through her mother’s influence. She was immediately aware of the differences between the Celtic practices of the Scots and the rest of the Roman Catholic world. Therefore, with loving reverence, strength, and virtue, she began to initiate change in the Church of Scotland. She was said to have had a great influence over her husband on account of her goodness and clarity of thought, so he supported her in the reforms. She was said to have regularly read to him from the Bible, since he was unable to read.

Queen Margaret convened synods to address the different practices of the Celts from the rest of the Roman Catholic Church, such as the time in which Lent and Easter were observed, the way Mass was celebrated, observance of the Lord’s Day, and the laws on marriage. In doing this, she strengthened ties to the pope in Rome, freeing the Scottish from their lengthy isolation. In addition to synods, Queen Margaret refurbished dilapidated churches, built new ones, and introduced Benedictine monks to Scotland by building the renowned Dunfermline Abbey, in which several Scottish monarchs were later buried. She is also known for her exceptional charity by which she fed the hungry, stooped down and washed the feet of the poor, cared for orphans, and organized religious education throughout the kingdom.

King Malcolm and Queen Margaret had eight children together, six sons and two daughters. Three of their sons went on to become kings of Scotland, one became an abbot, and a daughter became the Queen of England. In 1093, King Malcolm and Margaret’s oldest son, Edward, were killed in battle. When the forty-nine year old Margaret, bedridden in Edinburgh Castle due to ill health, heard the news, she died of grief three days later.

Jesus holds those with power and wealth to high standards: “Again I say to you, it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for one who is rich to enter the kingdom of God” (Matthew 19:24). Saint Margaret was as rich as one could be in her day, but she overcame the temptations of earthly wealth and power, and prayerfully devoted her life to the glory of God and the salvation of souls. She was a fitting representation on earth of the Queen of Heaven, the Mother of God, and she especially provides those of wealth and influence with an example they can follow.

Source: https://mycatholic.life/saints/saints-of-the-liturgical-year/november-16–st-margaret-of-scotland/