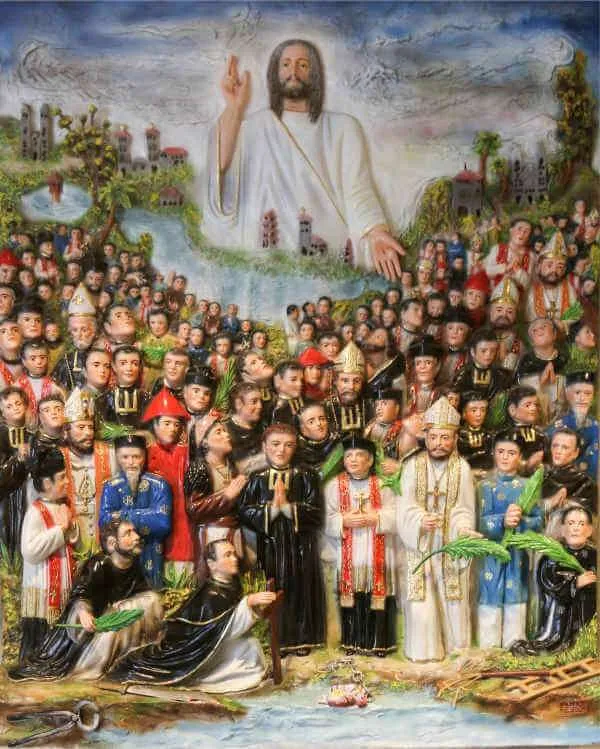

Seventeenth–Nineteenth Centuries; Patron Saints of Vietnam; Canonized by Pope John Paul II June 19, 1988

From the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, an estimated 130,000 to 300,000 men, women, and children; bishops, priests, and religious suffered martyrdom in Vietnam because they refused to renounce their Catholic faith. They were arrested, brutally tortured, and killed. Their torture was methodical, diabolical, and orchestrated to impose the maximum pain over the longest period of time possible. To escape that fate, all those arrested had to do was renounce their faith, step on a crucifix, or blaspheme Christ. If they did, they were granted kindnesses by the imperial courts. If they didn’t, their suffering grew more intense until they died.

In March of 1533, some records show that a European missionary named I-nê-khu (Ignatius—possibly a priest) began to preach the Gospel in Nam Định, northern Vietnam. In 1550, a Dominican priest is believed to have arrived in southern Vietnam, and between 1615 and 1627, Jesuits arrived. Among these early Jesuits, Fathers Alexander de Rhodes and Antoine Marquez, from Avignon, France, made the biggest impact by initiating the first formal program of evangelization. They arrived in 1627, and by 1630 they reported 6,000 converts. Though they were expelled from Vietnam twice, they completed a Romanized version of the Vietnamese alphabet and published a catechism and other liturgical books in Vietnam that enabled them and subsequent missionaries to communicate the faith in the local language. By 1660, there were an estimated 100,000 converts to Catholicism. Their success was attributed to their method of forming lay catechists who, in turn, spread the faith to their fellow citizens.

As the faith grew rapidly, suspicion arose among the feudal lords and others in the governing party. Christianity challenged practices in Buddhism, Confucianism, and ancestor worship, which were all central parts of Vietnamese culture. As the missionaries grew in popularity, there were also growing concerns that the Europeans might seek to colonize Vietnam. As fear and anger within the feudal lords and their ruling party began to reach critical levels, persecutions began. Actual records of all martyrs are lost to history. Andrew of Phú Yên, a nineteen-year-old Vietnamese catechist, is believed to have been the first martyr. In 1644, the local Mandarin ruler received orders from the feudal lord that he should expel the Jesuits and do what was necessary to stop the spread of “foolish opinions” of the Catholic faith. Andrew of Phú Yên was arrested at the home of Father de Rhodes and told to renounce his faith. He wouldn’t do so. He was beaten but exuded joy. He was then sentenced to death by hanging. Though his name was not included in the 1988 canonization, Andrew of Phú Yên was beatified in March 2000 and honored as the protomartyr of Vietnam.

Between 1659–1802, the Church in Vietnam began to be organized. In 1658, the Paris Foreign Missions Society was established, and two bishops were sent to form two dioceses. Shortly afterward, seven Vietnamese catechists were ordained priests, a women’s religious order was established, parishes were built, and the first Synod in Vietnam was held in 1670. Over the next seventy years, the Church in Vietnam continued to flourish with only minor persecutions and martyrdoms.

In 1742, Pope Benedict XIV issued an apostolic constitution which banned the ancestral worship and Confucian rites within the newly budding Asian churches of China, Japan, and Vietnam. This new restriction brought with it a serious wave of persecution in Vietnam. The imperial court saw this as an attack upon Vietnamese culture and society as a whole, since these Confucian rites were such an integral part of their national identity. Over the next sixty years, at least 30,000 Vietnamese Catholics were martyred as a way of trying to stop Catholicism’s growth. By 1802, there were three dioceses in Vietnam and approximately 320,000 Catholics.

In 1802, Emperor Gia Long unified north and south Vietnam and granted religious freedom to Christians. This was due, in large part, because Bishop Pigneau de Béhaine supported him in his ascension to the throne. However, his successor, Minh Mạng resumed the persecution of Christians in 1825. Though he sent a delegation to France to resolve the dispute and force the withdrawal of the missionaries, the French authorities ignored him. The next two emperors, Thiệu Trị and Tự Đức, increased persecutions. In 1868, Emperor Tự Đức issued a severe decree in which he divided his population into “good citizens—those who embraced traditional Vietnamese practices and religions” and “bad citizens—those who follow Christianity.” From 1820–1883, at least 100,000 Vietnamese Christians were martyred.

Within this period of persecution, a boy named Trần An Dũng was born into a poor non-Christian family. When he was twelve, his family moved to Hanoi to find work. In Hanoi, Trần met a Vietnamese catechist from whom he received shelter, food, and an education in the Catholic faith. Within a few years he was baptized, took the Christian name Andrew, and became a catechist. He was then chosen to study theology and was ordained a priest on March 18, 1823, at the age of twenty-eight. His priestly ministry led many to Christ. He fasted and lived a simple and morally upright life.

In 1835, Father Andrew was arrested but was ransomed by his parishioners using donations from the French Missionary Society. He then changed his last name to Lạc and moved to another territory to escape persecution. In 1839, however, he was arrested again, along with Fr. Peter Thi, whom Father Andrew was visiting so he could go to confession. They were both ransomed but arrested shortly afterward. This third time, they were brutally tortured, refused to renounce their faith, and so were beheaded in Hanoi on December 21, 1839. Father Andrew Trần Dũng-Lạc’s name is uniquely attached to this memorial as a representative of all Vietnamese martyrs, the 117 that are named, and the countless others who are unnamed and unknown.

In 1874, the French entered into the Treaty of Saigon, giving them control over southern Vietnam. In 1884, the Treaty of Huế was signed, which effectively reduced the Vietnamese emperor to a ceremonial role in the nation, with France taking control of the internal administration, military, and foreign policy. Though many citizens in Vietnam revolted against these treaties, French rule provided a safer environment for Catholics and missionaries, putting an end to the edicts of the previous century and the state-sponsored persecutions. Though some persecutions continued, they were more localized, rather than the result of imperial acts. Often, the Catholics were associated with the French colonizers, given that some of the missionaries were French, so rebellion against colonialism was sometimes taken out upon Catholics.

In addition to the 130,000 to 300,000 who suffered martyrdom between 1630–1886, countless others suffered as “confessors,” meaning, they suffered for the faith in ways that did not result in martyrdom. Many had to flee from their homes and villages, hide in the forests and mountains, or suffer exile to other countries, living in constant fear for their lives. Others had the words “ta dao,” meaning, “false religion,” written on their faces. Homes and property were confiscated, and whole villages were destroyed.

The French left Vietnam in 1954 after the defeat of French forces at Dien Bien Phu. A communist regime took control of the north, while a republic was formed in the south. As a result, there were mass migrations of Catholics to the south to avoid communist persecutions. After the Vietnam War ended in 1975 with the fall of Saigon, communism encompassed both north and south. Properties were confiscated, religious activity was restricted, priests and religious were imprisoned, and the government discriminated against lay Catholics.

Today’s memorial honors 117 martyrs who were initially beatified in separate groups: sixty-four in 1900, eight in 1906, twenty in 1909, and twenty-five in 1951. In 1988, Pope John Paul II canonized all these martyrs together, symbolizing the countless unnamed individuals who also gave their lives for their faith. Though the communist government of Vietnam failed to send delegates to the canonization of these holy martyrs, many thousands of exiled Vietnamese showed up in Saint Peter’s Square, and the very act of canonization resounded through the hearts and minds of the faithful within Vietnam. The group of 117 was made up of ninety-six Vietnamese, eleven Spaniards, and ten French. It includes eight bishops, fifty priests, and fifty-nine laypeople. Among the laypeople was a nine-year-old child, Saint Agnese Le Thi Thành.

As we honor this huge cloud of witnesses who gave their lives for their faith in a harsh and cruel environment, enduring some of the worst tortures ever committed in the history of the world, we are reminded that no matter how difficult life is, no matter how much we must endure, it is all worth it in the end. One of the martyrs who died in these persecutions was Father Jean-Théophane Vénard. He first became known through the writings of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux who had a deep devotion to him and was greatly inspired by his letters which were circulating at the time she was in the convent. Let’s conclude with a quote from Saint Théophane that Saint Thérèse copied and treasured: “I can find nothing on earth that can make me truly happy; the desires of my heart are too vast, and nothing of what the world calls happiness can satisfy it. Time for me will soon be no more, my thoughts are fixed on Eternity. My heart is full of peace, like a tranquil lake or a cloudless sky. I do not regret this life on earth. I thirst for the waters of Life Eternal.”

Source: https://mycatholic.life/saints/saints-of-the-liturgical-year/november-24—saint-andrew-dung-lac-and-his-companions-martyrs–memorial/