1891–1927; Invoked by the Mexican Church and in times of political persecution; Beatified by Pope John Paul II on September 25, 1988

Catholicism arrived in Mexico with the Spanish conquistadors in the early 1500s and rapidly grew, especially following the apparition of Our Lady of Guadalupe in 1531. By 1810, anti-Catholic sentiments had set in after Mexico’s independence from Spain when the Church became intimately intertwined with civil governance. The new Mexican Constitution in 1857 was the initial attempt by the newly independent state to limit the Church’s influence. Anti-Catholicism and anti-clericalism reached their peak in the 1920s under President Plutarco Elías Calles, leading to the Cristero Wars that took the lives of an estimated 50,000–250,000 Mexicans and brought the martyrdom of at least 40 priests. Of those priests, Blessed Miguel Agustín Pro, whom the Church honors today, was beatified by Pope John Paul II in 1988. Additionally, Saint Christopher Magallanes and his twenty-four companions, whose memorial is on May 21, were canonized by Pope John Paul II in the jubilee year 2000.

José Ramón Miguel Agustín Pro Juárez (Miguel Pro) was born in 1891, just before this painful period of anti-Catholicism in Mexico’s history. He was born in Guadalupe, Zacatecas, Mexico, the third of seven surviving children. When Miguel was still an infant, his family moved to Mexico City and would move around to various towns in the north over the next twenty years. Miguel’s parents were devout Catholics. His father was a respected and experienced mining engineer who often had a heavy workload and employed help from his children at times. As a youth, Miguel had a lively and attractive personality, along with a good sense of humor. He loved to tell stories and entertain others, and had a deep faith from an early age. He was especially close to his sister, María de la Concepción, with whom he made a pact that he would become a Jesuit priest and she a nun. They both fulfilled that pact. Later in life, letters exchanged between the two reveal their deep faith and respect for each other.

At the time of Miguel’s birth, the 1857 anti-Catholic Mexican Constitution had been in place for about twenty-five years. President Porfirio Díaz permitted the Church to operate independently and freely, while leaving the laws on the books. By the time Miguel turned twenty, political instability had risen, leading to Díaz’s resignation and exile in 1911. In that same year, Miguel entered the Jesuit novitiate in El Llano, Michoacán, Mexico. The next three years saw two short-term presidents, and in 1914, Venustiano Carranza seized power and took the title of “First Chief of the Constitutionalist Army.” The Jesuit novitiate in El Llano was closed as part of renewed anti-Catholic persecutions. Brother Miguel fled to the United States, then to Spain, and finally to Belgium. For the next ten years, Brother Miguel studied as he moved, preparing for priestly ordination that took place in Belgium in 1925. Though his formation was fraught with illness, exile, and concern for his homeland, he kept his eyes upon God’s will and embraced the gift of the priesthood with great joy. “I could not hold back the tears on the day of my ordination, above all at the moment when I pronounced, together with the bishop, the words of the consecration.”

During the period that Father Miguel was outside Mexico in formation, things went from bad to worse for the Mexican Church. In 1917, a new Mexican constitution imposed more stringent restrictions on the Church. The education of youth was restricted to secular schools. Religious ceremonies were prohibited from taking place outside of churches. Religious organizations were prohibited from owning any property other than churches, leading to widespread confiscation. Monastic vows were prohibited. Clergy could not inherit property and were stripped of citizenship, the right to vote, and the ability to participate in politics. Finally, only native-born clergy were allowed to minister; foreign clergy were forced to leave.

In 1925, Plutarco Elías Calles was elected president and soon after ushered in a more intense era of anti-Catholic and anti-clerical persecutions. He enforced the 1917 constitution and, in 1926, enacted the “Law for Reforming the Penal Code,” also known as the “Calles Law,” which required stricter enforcement of the Constitution. All forms of public worship were outlawed, the remaining Church property was confiscated, all forms of religious education (even private) were forbidden, and priests were expelled from the country. This led to a peasant revolt called the Cristero Wars, which lasted until 1929. “¡Viva Cristo Rey! ¡Viva la Virgen de Guadalupe!”—“Long live Christ the King! Long live the Virgin of Guadalupe!”—This was the cry of the Cristeros in the face of oppression.

As the 1926 persecution began in earnest, the newly ordained Father Miguel Pro could do nothing from Belgium, except pray. He devised a plan to return to Mexico and live publicly as a well-dressed businessman, mechanic, or even beggar, while at the same time carrying out a clandestine ministry. He had never lived in Mexico as a priest, so he believed he could escape the notice of the civil authorities. He arrived in Mexico on July 8, 1926, and made his way to Mexico City where he began his priestly service. His naturally joyful personality and sense of humor helped inspire many and lifted the heavy burden of the oppression they were experiencing. He conducted Masses in secret, heard confessions, administered the other sacraments in private homes, and moved around to avoid getting caught by the authorities. After a few months of his clandestine ministry, Father Miguel was arrested on suspicion that he wrote pamphlets and attached them to 600 balloons that were released over the city to share the Gospel with the people. After being interrogated, he was released because there was insufficient evidence to hold him. When another arrest warrant was issued for him shortly after, he remained in seclusion but resumed his secret ministry once his superiors gave their consent.

Less than a year later, in November 1927, an assassination attempt resulted in the wounding of the former president Álvaro Obregón. The authorities traced the car that was used to Father Miguel’s brother, who had nothing to do with the plot. Nonetheless, the authorities moved in and not only arrested Father Miguel’s two brothers but also Father Miguel. Another man confessed to the crime, stating that he acted on his own, without any involvement by the Pro brothers. After the brothers were questioned in Mexico City by the Detective Inspector, President Calles himself gave the order to execute Father Pro and his brothers, despite there never having been a trial. President Calles gave further orders that the execution was to be photographed and printed in the papers the following day as a way of deterring the Cristeros in their revolution.

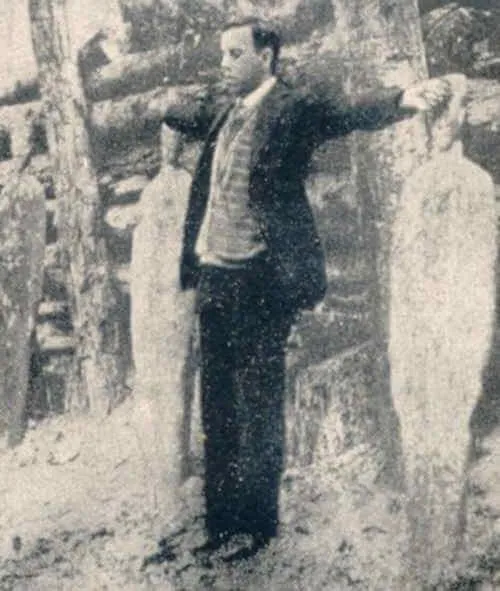

On November 23, 1927, Father Miguel Pro walked from his cell to the courtyard where the firing squad awaited, with the photographer ready at hand. The pictures show a confident and courageous Father Miguel Pro, kneeling before his executioners, facing them without a blindfold, forgiving them, blessing them, holding a rosary in one hand, and a crucifix in the other. He cried out, “May God have mercy on you! May God bless you! Lord, You know that I am innocent! With all my heart I forgive my enemies!” He then rose, faced the firing squad, extended his arms as if on a cross, and prayed in a loud voice, “Viva Cristo Rey!” After the shots rang out, Father Pro was still alive, so one of the soldiers came forward and shot him point-blank.

When the pictures and story appeared the following day, the Mexican people were deeply inspired by their young martyr. Though publication in the papers was meant to be a deterrent to the Cristeros, the pictures and story had the opposite effect. An estimated 40,000 people lined the streets for Father Pro’s funeral procession. Even though neither a Catholic funeral Mass nor the rites of burial were permitted, an estimated 20,000 Cristeros prayed at the cemetery as his body was buried.

Blessed Miguel Pro fell in love with his Lord during a time of extreme persecution. Rather than shying away from his faith, he prayed and fulfilled his priestly ministry with courage and love. His life culminated with a choice either to be bitter or to forgive and hope in his God. He chose the latter. May his life and witness inspire all who are persecuted for their faith, and may his prayers assist you on your own journey when times are rough.

Source: https://mycatholic.life/saints/saints-of-the-liturgical-year/november-23—blessed-miguel-agustn-pro-priest-and-martyr—optional-memorial/