Late Second Century–c. 223; Patron Saint of cemetery workers; Pre-Congregation canonization

Saint Callistus (also spelled Callixtus) is known to us primarily through his detractors, both of whom are considered heretics. One was a priest named Hippolytus of Rome, who later set himself up as an antipope in opposition to Pope Callistus. The other detractor was Tertullian, an early Christian writer and theologian who was initially orthodox and is even credited with first using the word “Trinity,” but who later followed the heresy of Montanism.

Based on their writings and on other later sources, Callistus was a slave in Rome, perhaps born of a slave mother. At that time, slavery was common. Criminals, captives of war, victims of piracy, and children born into slavery made up the slave population. The Roman Empire of the third century permitted slavery but also had laws forbidding harsh treatment and offered slaves ways of buying their freedom. As Christianity emerged, it often advocated for fair treatment of slaves and for their personal dignity, which is found even in the writings of Saint Paul.

Late in the second century, a Christian named Carpophorus is said to have collected money from other Christians to be used to care for widows and orphans. His slave, Callistus, was put in charge of the money, but he lost it and fled the city in fear. He was found due west of Rome on a ship waiting to set sail in the Mediterranean Sea. When he learned that he was found, he jumped overboard but was captured and returned to his master. He was later released, perhaps because his captors thought he would lead them to the money he lost. However, after his release, Callistus stirred up a controversy in a synagogue and was arrested and sent to work in the mines of Sardinia. Eventually, he was released at the request of the empress who was sympathetic to Christians.

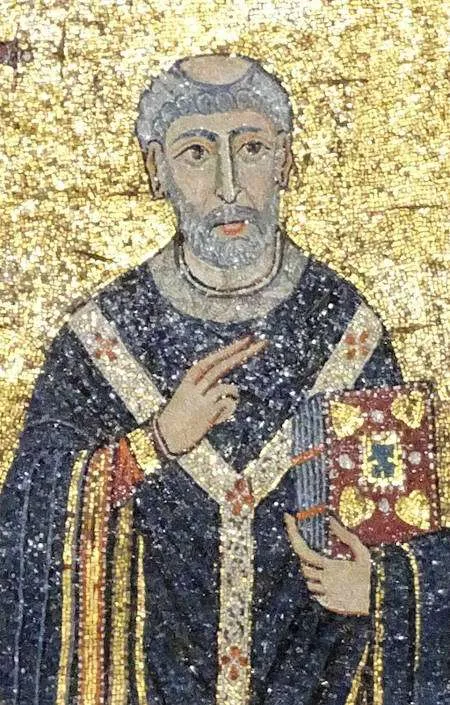

After Callistus was released, the Christians entrusted him to the care of Pope Victor while he recovered from ill health. Pope Victor died around c. 199, and Callistus remained in the service of the pope’s successor, Pope Zephyrinus, who ordained him a deacon. At that time, deacons had great responsibility, and Deacon Callistus was no exception. He was appointed by the pope as the caretaker of an underground Christian cemetery on the Appian Way.

The Catacombs of Saint Callistus, as they are called today, were a massive multi-level underground cemetery used primarily for Christians from the second to fourth centuries. The tunnels span several miles and remain a popular place of pilgrimage. It is estimated that as many as a half million people are buried there. Burials included several early popes and beloved Roman martyrs, making the catacombs an important place of prayer.

Around the year 217, Pope Zephyrinus died and Deacon Callistus was chosen as his successor. By God’s grace, he had gone from slavery, to prisoner, to freeman, to deacon, to pope! Pope Callistus was a man of great compassion. Perhaps the sufferings, and even sins, that marked his early life inspired him to have a merciful heart. One question that had emerged at that time was what to do with those who had engaged in public sins but later repented. Some of these sinners had joined a heretical sect, engaged in adultery, or had succumbed to imperial decrees mandating emperor worship and the worship of Roman gods. Some priests, such as Hippolytus, revolted at the idea of leniency, especially for sexual sins. As a result, Hippolytus set himself up as a rival, or antipope, the first antipope in the history of the Church. Tertullian also opposed Pope Callistus, arguing that the power to bind and loose from sins was a power given only to Saint Peter by Jesus, but not to his successors.

Among his other pastoral achievements, Pope Callistus reinvigorated the practice of Ember Days, which were days of fasting at the beginning of the four seasons as a way of beseeching God for blessings in each of those seasons. He is said to have been a diligent evangelist, converting and baptizing many people of prominence, such as soldiers and senators, most of whom later died as martyrs.

During the reign of Roman Emperor Alexander Severus, a persecution of Christians broke out in the empire, especially in Rome. A Roman priest named Calepodius was tortured and thrown into the Tiber River with a millstone tied around his neck. Pope Callistus found his body and buried it in a catacomb. Afterwards, one tradition states that Calepodius appeared to the pope and prophesied the pope would soon die by martyrdom. Shortly afterwards, Pope Callistus was arrested, starved for a week, tortured, and then thrown into a deep well with a stone around his neck. Pope Callistus’ body was later recovered and buried next to Calepodius. In the ninth century, both of their bodies were transferred to the Church of Santa Maria in Trastevere.

It has been said of Saint Callistus that if we knew more about his life from Christian sources, he might have gone down as one of our greatest popes. He suffered greatly in his early life but entered the service of the Church where he became a deacon and then pope. He taught about the importance of penance, evangelized, faced calumny and persecution with courage, and died for his faith. What little we know of his life remains an inspiration today, and his merciful commitment to repentant sinners shines forth as the law of Christ and the ongoing practice of the Church.

As we honor this ancient pope, ponder your own approach to mercy. Mercy is two-sided. We need to be convinced of God’s mercy toward us, and we need to show that same depth of mercy toward others. Pray to Saint Callistus today for a merciful and courageous heart so that you will follow in his footsteps.

Source: https://mycatholic.life/saints/saints-of-the-liturgical-year/october-14–st-callistus-pope-martyr/