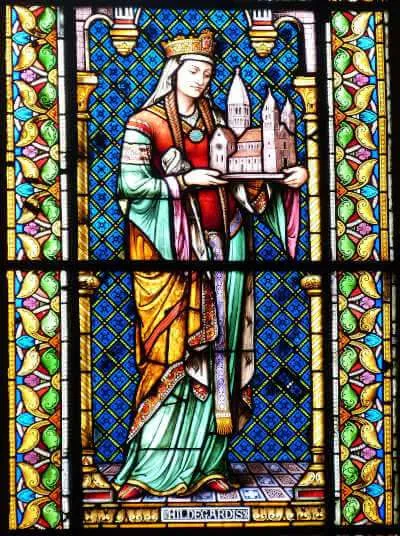

1098–1179; Patron Saint of philologists and Esperantists; Canonized by Pope Benedict XVI in 2012 (equipollent canonization); Declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope Benedict XVI in 2012

Feudalism, characterized by relationships structured around landholding in exchange for service or labor, was the defining characteristic of the socio-economic system in Europe between the ninth and fifteenth centuries. Within the feudal system, the monarch, princes, dukes, counts, and their immediate family members—known as the upper nobility—were the primary landowners and rulers. Below them were the lower nobility who often managed less land and served the upper nobility as knights, barons, and lesser lords. Depending on their rank, these nobles ruled over territories known as kingdoms, principalities, and duchies. It was within this complex feudal system, with its intricate hierarchy and blend of secular and ecclesiastical authority, that today’s saint was born.

Saint Hildegard of Bingen was born to parents of lower nobility in the village of Bermersheim vor der Höhe, within the Duchy of Franconia, modern-day Germany. Her father was in the service of Count Stephan II of Sponheim, a powerful member of the upper nobility. Hildegard, the tenth child in her family, was offered to the Church as a tithe by her parents when she was eight years old, as was the custom at that time. She was given to the Benedictine monastery at Disibodenberg, about twenty-five miles from her hometown, and was cared for by Jutta von Sponheim, the daughter of Count Stephan II.

Jutta was only six years older than Hildegard. When Jutta was fourteen, she became a hermit next to the men’s Benedictine monastery of Disibodenberg and eventually the magistra, or abbess, of the women’s branch. Despite Hildegard’s sickliness as a child, Jutta taught her to read Latin well enough to pray the Psalms and Divine Office. Jutta also taught basic catechism and helped to form Hildegard’s life of faith, devotion, and asceticism. Hildegard also learned to play the psaltery, a primitive form of the harp. As Jutta was also of noble descent, she was in a unique position to understand Hildegard and help her on a personal level. Together, they inspired other noble girls to join them. In 1112, after about seven years with the Benedictines, Hildegard took the Benedictine veil under Bishop Otto of Bamberg at the age of fifteen.

In 1136, Abbess Jutta died and Hildegard, at the age of thirty-eight, was elected abbess. Over the next fourteen years, the community continued to grow under Abbess Hildegard’s leadership. By 1150, she had moved her community to Rupertsberg, near Bingen, and later established a second monastery at Eibingen in 1165.

Though Hildegard entered religious life, she received a good—although limited—education. Despite this, she developed vast knowledge in numerous areas, which points first to her high intelligence. However, her knowledge was also infused by what she referred to as “the shadow of the living light.” This “living light” came to her in the form of mystical visions and inspirations from a very early age. She mostly kept these mystical experiences to herself until she was in her forties. During those earlier years, she absorbed this mystical knowledge, pondered it, allowed it to grow and deepen, so that it formed who she later became. More than anyone else, her Teacher was the Holy Spirit, and her knowledge was a divine infusion of Truth that flooded her mind and gave her a supernatural understanding of Scripture, life, God, Heaven, hell, sin, Christ, and the entirety of revelation. Her supernatural knowledge even gave her insight into the natural sciences.

In 1142, at the age of forty-four, Abbess Hildegard intensely sensed God commanding her to begin writing her visions and sharing her divinely infused knowledge. The rest of her life would be spent transcribing all that she understood by this infusion of the living light. The clarity, specificity, and depth of her visions prove that they could only originate from the Holy Spirit. Her first work, completed in 1151, was a written description of twenty-six visions with her commentary on them known as Scivias—“Know the Ways.” These visions and commentaries touch on the creation of the world, the nature of God, Heaven and hell, angels and demons, humanity, the Incarnation, Scriptural interpretations, the fall, redemption, the Church, Sacraments, the end of time, and much more. She offered a summary of all of salvation history in specific and profound language.

After completing her first great visionary work, Hildegard spent the next twenty-eight years writing extensively. She completed two more major visionary works in which she dealt with virtue and vice, God’s relationship with man, and God’s activity in the world. She also wrote in detail on natural sciences, medicine, and women’s health, despite her lack of formal education in these areas. Furthermore, she wrote on the saints and the Rule of Saint Benedict. She penned numerous letters to popes, emperors, abbots, abbesses, and others. She was also an artist and musician, composing beautiful hymns and setting them to music, accompanied by illustrations in the manuscripts. Many of her compositions, with their soaring melodies and beautiful harmonies, are still sung today.

Though Abbess Hildegard lived within the walls of her monastery, she was frequently called upon for counsel by the universal Church. She was often invited to preach in public squares and cathedrals, unusual for women at that time. Her writings were examined and approved by Pope Eugene III and were examined and praised by Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, Hildegard’s contemporary.

Saint Hildegard was officially declared a saint and Doctor of the Church in 2012 by Pope Benedict XVI, even though she had informally been recognized as a saint since the time of her death. Given this recent honor, Saint Hildegard’s writings should be seen as especially relevant for the Church today. Her profound mystical and apocalyptical-like wisdom sheds light for us on many of the deepest mysteries of life.

As we honor this great saint and recent Doctor of the Church, ponder the fact that all true wisdom and knowledge come only from God. The most brilliant minds and greatest scientific advancements will forever pale in comparison to the revelations of God. Seek that wisdom, open yourself more fully to the truths of God, and pray that “living light” of God will teach you all you need to know to be of greater service to His perfect plan for your life.

Source: https://mycatholic.life/saints/saints-of-the-liturgical-year/saint-hildegard-of-bingen/