Patron Saint of clergy, Canonized by Pope Alexander III on February 21, 1173

In December 1154, twenty-one-year-old Henry II became King of England. At that time, England and Normandy had just ended a period of civil war, referred to as “The Anarchy.” As a result, England was politically divided and weakened. The new young king urgently needed a capable and strong chancellor to help him as he worked to reunite the kingdom, assert control, and implement legal and administrative reforms.

For this daunting task, Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury recommended his archdeacon, Thomas Becket, for the job. The king accepted his recommendation, and Archdeacon Thomas Becket became the second most powerful civil authority in England.

As chancellor, Thomas oversaw the administration of the royal chancery, including the creation and issuance of official documents. He served as an important legal advisor to the king, held responsibility for the highest court of appeals, was the chief diplomat, represented the king in foreign and Church matters, and assisted in the kingdom’s financial matters.

Chancellor Thomas Becket and King Henry II not only worked well together in the administration and reformation of the kingdom, they also became close friends. They enjoyed riding together, hunting, indulging in a luxurious lifestyle, and every form of comradery. Becket’s administrative skills helped the king reassert his control over the kingdom and even portions of the Church.

The two fought side by side in battles and were said to be of one mind and heart in all that they did. Although Chancellor Becket retained his status as a deacon, his lifestyle was notably secular. Despite this, he was widely recognized as a man of faith and purity, even amidst his indulgences and various excesses.

In 1161, six years after Deacon Thomas became Chancellor of England, Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury died. The Archdiocese of Canterbury was the most important diocese in England, and the archbishop was considered the senior English bishop. Desirous of exerting even more influence and control over the Church in England, King Henry wanted his close friend, Chancellor Thomas Becket, to become archbishop.

Henry presumed that Thomas would continue to act as his chancellor, helping the king to make further inroads into the Church’s governance. Thomas, however, was staunchly opposed to the idea. He knew of Henry’s intentions for the Church, and Becket also knew that if he were the archbishop, he would have to fulfill that role with the same strength as he had fulfilled the role of chancellor.

In other words, he knew he would have to defend the Church against King Henry. The king appointed him anyway, and the pope confirmed his appointment. In June 1162, Becket was first ordained as a priest and, the very next day, consecrated as a bishop, assuming the role of Archbishop of Canterbury.

Within a year of his consecration, Archbishop Thomas began a profound spiritual transformation. He shed the luxuries he was accustomed to, devoted himself to prayer, fasted, and did penance. While the king wanted Thomas to remain as Chancellor of England so as to unite the two roles in one person at the service of the king, the archbishop refused and resigned his chancellorship. This angered the king, and their close friendship immediately began to suffer.

Over the next year and a half, King Henry and Archbishop Thomas began to clash. The archbishop attempted to regain church property that had been seized by the king, asserted the independence of the Church, and argued that clerics who violated the law could only be tried in Church courts, not civil. In response, Henry began to harass the archbishop, impose arbitrary fines on him, and make false accusations of embezzlement.

In January 1164, King Henry issued sixteen decrees, known as the Constitutions of Clarendon, that sought to limit the powers of the Church and expand state authority. He required the bishops to consent to these decrees. While some bishops acquiesced, Archbishop Thomas Becket staunchly opposed them. In October of that same year, the king formalized his accusations and put Archbishop Thomas on trial in Northampton Castle.

In a sham trial, Becket was found guilty of contempt of royal authority and misappropriation of funds during his time as Chancellor. With a guilty verdict, the king demanded Becket resign his archbishopric, which he refused to do. Instead, he hid and sailed to France where he took refuge in the court of King Louis VII. Shortly afterwards, Becket traveled to Sens, France, where Pope Alexander III was living in exile. The pope offered Archbishop Thomas his full support and permitted him to live in the Cistercian Abbey of Pontigny in Burgundy while negotiations took place with King Henry.

Over the next four years, negotiations among King Henry II, Pope Alexander III, and Archbishop Thomas Becket continued but made little progress. The archbishop continued to firmly oppose the Constitutions of Clarendon, and the king continued to insist on them. Archbishop Thomas did make some minor concessions, but it wasn’t until the pope sent a delegation to Henry that Henry finally agreed to permit Becket to return to Canterbury.

The faithful were overjoyed at the return of their archbishop, but soon after, tensions flared when Archbishop Becket excommunicated three bishops. These bishops had crowned King Henry’s son as the future king, an act traditionally reserved for the Archbishop of Canterbury, thus infringing upon his rights. When King Henry learned of the excommunication, he sent four knights to bring the archbishop to Winchester where he was to defend his actions.

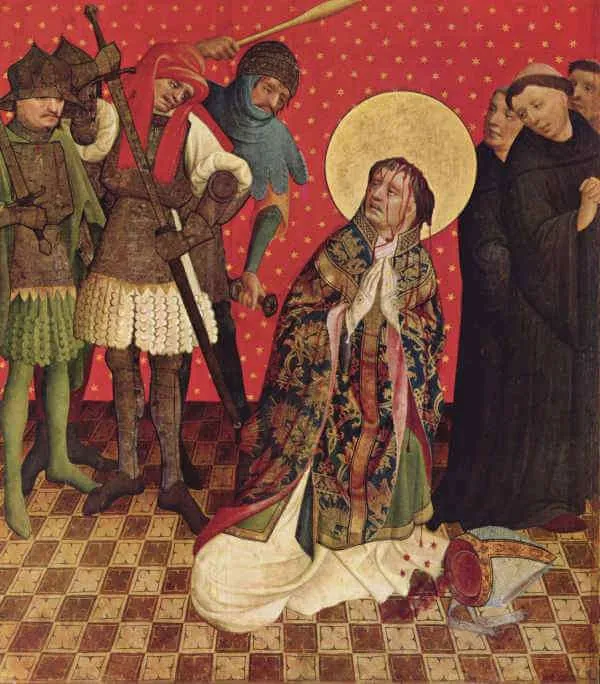

One tradition states that as the king gave his orders to the knights, he angrily said, “Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?” The knights confronted the archbishop in his cathedral, but the archbishop refused to go with them. They then gathered their weapons and charged into the church saying, “Where is Thomas Becket, traitor to the King and country?”

As soon as they reached him, the knights began to split open his skull while he clung to a pillar in the cathedral as the monks sang Vespers. His final words were, “For the name of Jesus and the protection of the church, I am ready to embrace death.” His brains spilled upon the cathedral floor, and a cleric who accompanied the knights then stepped upon Becket’s neck saying, “We can leave this place, knights, he will not get up again.”

Archbishop Becket was immediately praised as a martyr, and veneration of him quickly spread across England. Three years after Thomas Becket’s death, Pope Alexander III declared him a saint. Four years after Thomas Becket’s death, King Henry visited the saint’s tomb and did public penance for the role he played in his death. Saint Thomas Becket’s tomb became a popular place of pilgrimage in Europe, and numerous miracles were attributed to his intercession.

As we honor this heroic archbishop and saint of God, ponder the firm resolve that Saint Thomas had in defense of the Church. Guided by divine inspiration, he knew in his heart the necessity to resist the king’s unjust intrusion into the Church’s governance and administration. Honor Saint Thomas by invoking his intercession, praying fervently for the universal right to worship God freely, and for the Catholic Church’s liberty to spread the Gospel and administer the Sacraments unhindered.

Source: https://mycatholic.life/saints/saints-of-the-liturgical-year/29-december-saint-thomas-becket-bishop-and-martyr–optional-memorial