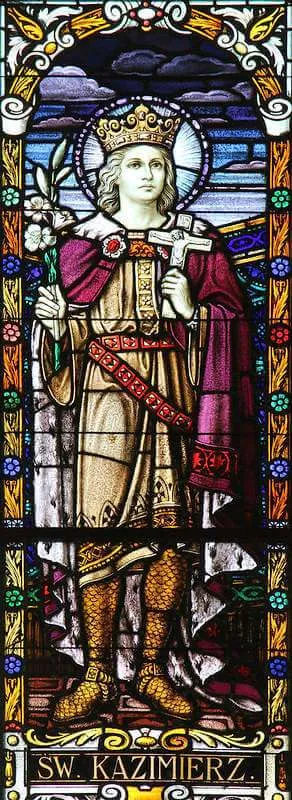

King Casimir IV was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania. His wife, Queen Elizabeth, was the daughter of the Holy Roman Emperor Albert II. Their marriage was arranged primarily for political reasons, giving King Casimir IV greater influence in Bohemia and Hungary, but their marriage also bore great spiritual fruit. They had thirteen children, the third being the saint we honor today, Saint Casimir, named after his father.

Saint Casimir was born on October 3, 1458, the second son and third child in the Polish royal family. King Casimir IV’s father had converted to Catholicism from paganism and introduced Christianity to Lithuania. King Casimir IV was, therefore, raised in a good Catholic home which he also provided to his children. A faithful Catholic herself, Queen Elizabeth was the loving mother of her thirteen children.

As children born into royalty, Casimir and his siblings were well educated. From the age of nine until sixteen, Casimir and his older brother were tutored by a Polish priest named Father Jan Długosz. This good priest taught the boys Latin, German, law, history, rhetoric, and classical literature.

Casimir had no desire for power, war, riches, or nobility. Father Długosz had taught him well, and Casimir had fallen in love with his God and the Blessed Virgin. He prayed frequently, often slept on the floor, engaged in other penitential practices, spent entire nights meditating on the Passion of our Lord, dressed simply, and desired to live a life of chastity. He was charitable to the poor, manifested the virtues, and edified all who encountered him. He especially had a deep devotion to our Blessed Mother and each day sang an ancient hymn called, “Daily, Daily Sing to Mary.”

When Casimir was only thirteen, the King of Bohemia and Hungary died and King Casimir IV asserted his right to name a successor. The Bohemians agreed and accepted Vladislaus, the King’s firstborn son, as their king, but some of the Hungarians did not, preferring a godless tyrant named Matthias Corvinus. With the support of some of the Hungarian nobles, King Casimir IV decided to name his son Casimir to the Hungarian throne by force. Casimir was sent to lead the Polish army in battle against the Hungarians and take the throne. Casimir agreed out of obedience to his father, but his heart was not in it. He opposed the war, and in time the effort failed and Casimir returned to Poland. His opposition grew even stronger when he heard that Pope Sixtus IV had asked his father not to go to war. Upon Casimir’s arrival home, his father was furious and imprisoned him in a tower for three months. Those three months, however, were just what Casimir longed for.

In the solitude of imprisonment, Casimir was able to return to his life of prayer and deepen his union with God. Afterward, he continued his studies and life of devotion, vowing to remain celibate for the Kingdom of God. His father was not pleased and attempted to arrange a marriage for him, but he refused. After completing his studies at the age of sixteen, Casimir worked closely with his father, but his heart remained with God and the Blessed Mother. When Casimir was twenty, his father had to be absent from Poland for about five years, tending to matters in Lithuania. During those years, Casimir was put in charge of ruling Poland, which he did with thoughtfulness, justice, and charity. When Casimir was twenty-five, he became ill with a lung disease. His father rushed back to Poland to be with his son, and on March 4, 1484, at the age of twenty-five, Casimir died.

After his death, devotion to Casimir quickly exploded. Many people prayed to him, and many attributed miracles to his intercession. One notable miracle took place in 1519 when the Lithuanian army was engaged in battle with the Russians. It is said that Saint Casimir appeared to the Lithuanian soldiers in a vision and directed them to a place where they could best defend their city, which they successfully did. This might be the reason that Saint Casimir is the patron saint of both Poland and Lithuania.

Shortly after that miracle, it is believed that Pope Leo X carefully examined Casimir’s life and miracles and was prepared to canonize him, but might have died before he was able to do so. Therefore, his successor, Pope Adrian VI, might have been the one to canonize him. Because those questions remained for some time, Pope Clement VIII officially confirmed Casimir’s canonization in 1602, adding him to the Roman liturgical calendar for Poland and Lithuania. In 1620, Saint Casimir was added to the Roman Calendar of the universal Church.

Worldly power, riches, and honors were all within the grasp of this young prince, yet he chose the power, riches, and honors bestowed by the heavenly King instead. His heart was filled with faith from a very early age that only grew as he got older. Even after Casimir’s death, God used him to inspire many. Ponder your own ambitions in life, and seek to imitate this young prince who rejected the lies of this world, preferring only the eternal truths of the Kingdom of God.

Source: https://mycatholic.life/saints/saints-of-the-liturgical-year/march-4-saint-casimir/