The Immaculate Heart of Mary was created around 15 BC as a result of the Immaculate Conception, which is a dogma of our faith. As The Immaculate Conception, the Blessed Virgin Mary was preserved from all sin from the first moment of her conception by a singularly unique grace, preemptively bestowed upon her by the merits of her Son’s life, death, and resurrection. From the moment of her Immaculate Conception, Mary remained free from all sin as a result of her own free choice to cooperate with grace. As a result, she was conceived as a suitable instrument for the Incarnation of God, and she remained a suitable instrument throughout her life.

After Jesus’ birth, the Mother of God continued to perfectly cooperate with grace, accompany her Son, stand at the foot of His Cross, jointly offer Him to the Father, experience His Resurrection and His Ascension into Heaven, participate in the full outpouring of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, and help give birth to the nascent Church through her motherly care. At the completion of her life, she was taken body and soul into Heaven to be with her Son and to be crowned as the Queen of Heaven and Earth, from which she mediates the love and mercy of God, and will do so for all eternity. The immaculate nature and this full view of our Blessed Mother’s life is the “big picture.” Today, we celebrate one specific aspect of that big picture—her Immaculate Heart.

Honoring the Immaculate Heart of Mary leads us to ponder that which she pondered—her own heart filled with perfect love. We first receive a glimpse of her heart in the Gospel of Luke. After the angels appeared to the shepherds in Bethlehem and announced the birth of Christ, they went in haste to where Jesus was born and found Mary, Joseph, and the Child lying in a manger. They told Mary and Joseph about their experience of the angel, “And Mary kept all these things, reflecting on them in her heart” (Luke 2:19). Twelve years later, Mary and Joseph traveled to Jerusalem from Nazareth for the annual feast of Passover. After completing the customary prayers and sacrifice, they began their journey home, thinking Jesus was in the caravan with relatives. When they discovered He was not, they returned to Jerusalem to find twelve-year-old Jesus talking with the teachers in the temple and asking them questions, and “all who heard him were astounded at his understanding and his answers” (Luke 2:47). After inquiring of Jesus why He remained, He told them He had to be in His Father’s house. Though Mary and Joseph did not fully understand the mystery they were witnessing, “his mother kept all these things in her heart” (Luke 2:51).

Every other encounter between Jesus and His mother in Scripture also reveals a sense of mystery and awe that evoked love and pondering. Most notably, as Jesus hung on the Cross, His mother stood before Him, gazing with love. From the Cross, Jesus entrusted Mary to John, and through John, to the whole Church.

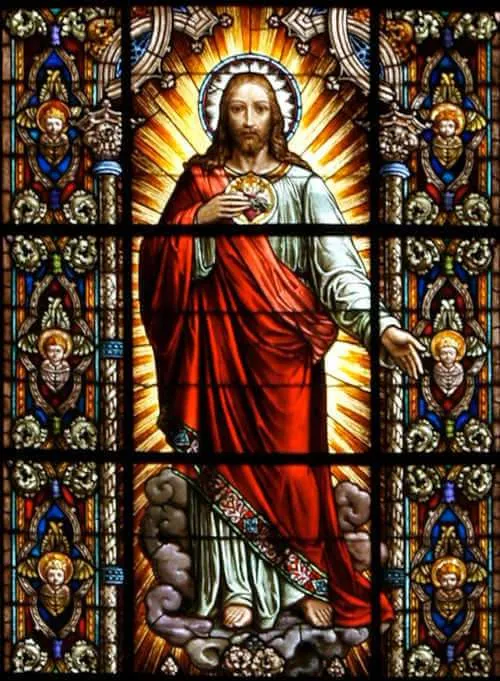

Because the Mother of God was and is the Immaculate Conception, free from all sin throughout her life, then every part of who she was and is remained immaculate, including her heart. Mary’s heart, as with every human heart, is a symbol of every relational virtue that enables one to love. The Mother of God’s human love for her Son was perfect. And that is something worth pondering! Prior to the Mother of God and her Son, the perfection of human love did not exist. From the time of Adam and Eve, human love was mixed with selfishness and sin. From the moment of the Incarnation, the perfect exchange of human love was established between the Mother of God and her divine Son. Today we celebrate that perfect love and are invited to ponder it and share in it.

As a result of Jesus entrusting His mother to John and the whole people of God and her subsequent Assumption into Heaven and coronation as Queen, we also ponder the perfection of human love for us, her children, that flows from Heaven. By God’s will, that perfection of love is bestowed upon the Church and all Her members through the Immaculate Heart of Mary. We must not only ponder this glorious reality, we must also do all we can to be receptive sons and daughters of the love of our heavenly mother who loves us with a perfect love and bestows upon us the pure and perfect love of her Son’s divine grace that was instilled in her Immaculate Heart.

Devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary began in apostolic times and continued through great saints, such as Ephrem the Syrian, Cyril of Alexandria, John Damascene, Gregory of Nazianzus, Ambrose of Milan, Augustine of Hippo, and Jerome. Though they did not make specific reference to the Immaculate Heart, they spoke of the Blessed Mother’s many virtues. These saints especially helped to lay the foundation for proclaiming Mary as the Mother of God (Theotokos) at the Council of Ephesus in 431.

From the twelfth to the fifteenth centuries, a number of saints contributed to the deeping of our understanding of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Among them are Saints Anselm of Canterbury, Bernard of Clairvaux, Mechtilde, Gertrude the Great, Bridget of Sweden, and Bernardino of Siena.

From the sixteenth century to the twentieth centuries, many other saints continued to develop our understanding of the Blessed Virgin Mary. In 1648, Saint John Eudes, a French priest and founder of the Congregation of Jesus and Mary, instituted a local feast in honor of the Holy Heart of Mary, fostering a realization of the love that the Blessed Mother had for her Son and for all people. This was the first liturgical feast approved by a local ordinary specifically honoring the “Holy Heart of Mary.” After him, Saints Louis de Montfort and Alphonsus Liguori wrote extensively on the Blessed Virgin Mary.

In 1854, Pope Pius IX proclaimed the Dogma of the Immaculate Conception, which paved the way for the specific title of the Immaculate Heart, and in the early twentieth century, Saint Maximilian Kolbe wrote extensively on the Immaculata.

In 1916, an angel appeared to three children in Fátima, Portugal, speaking of the “infinite merits of the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus and of the Immaculate Heart of Mary.” The following year, the Blessed Virgin Mary, under the title of “Our Lady of the Rosary,” appeared six times to the children. During the second apparition, Our Lady said that Jesus “wishes to establish in the world devotion to my Immaculate Heart.” In 1925 and 1929, Our Lady appeared again to Lúcia to ask that her Immaculate Heart be honored on the first Saturday of each month.

In 1944, Pope Pius XII instituted the universal feast of the Immaculate Heart of Mary to be celebrated annually on August 22, and in 1969, Pope Paul VI moved the celebration to the Saturday after the Solemnity of the Sacred Heart.

As we honor the holy, most pure, and Immaculate Heart of Mary, try to ponder that which the Blessed Virgin Mary pondered during her life. Ponder the love she had for her Son. Ponder the mysteries contained within her heart. As you do, especially ponder the love that her heart has for you. Only in Heaven will we fully understand the holiness of Our Lady’s Immaculate Heart. For now, we must foster devotion to all that is contained within it and seek to open ourselves to the ongoing outpouring of God’s grace that dwells in an immaculate way in that holy sanctuary of love.

Source: https://mycatholic.life/saints/saints-of-the-liturgical-year/immaculate-heart-of-mary–memorial/