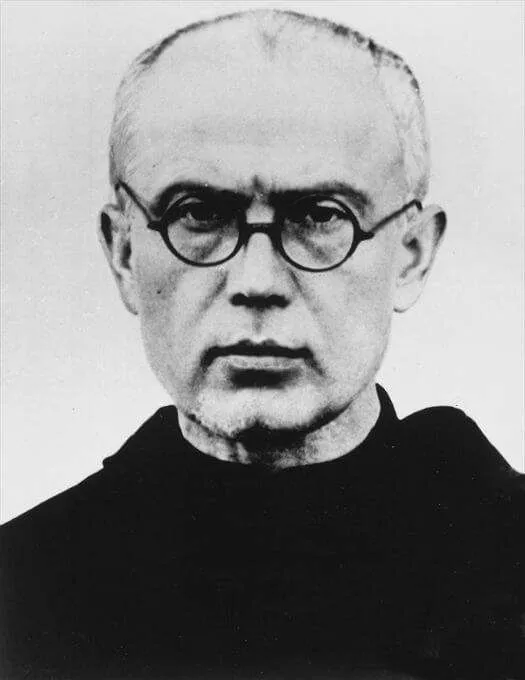

Saint John Eudes, Priest

1601–1680; Patron Saint of Eudists, Order of Our Lady of Charity; Diocese of Baie-Comeau; and Missionaries; Canonized by Pope Pius XI on May 31, 1925

In France, in 1562, tensions ran high between the Catholic majority and the Protestant Calvinist minority. Calvinism was spreading and opposition was fierce. This resulted in violent clashes from 1562–1598 in the Wars of Religion. Although the wars were primarily driven by powerful noble families, many citizens got involved, leading to multiple massacres. In 1589, Henry of Navarre, a Calvinist, ascended the throne to become King Henry IV of France. Despite his Calvinist roots, Henry converted back to Catholicism to secure his reign and to establish peace. He issued the Edict of Nantes in 1598, which granted religious tolerance to Protestants, effectively ending the internal wars. Three years later, Saint John Eudes was born.

John Eudes was born in Ri, a small farming village in the Normandy region of northwestern France. The region’s fertile soil produced abundant crops of wheat, barley, and fruit. John had two younger brothers and four sisters, and his parents were devout Catholics. Following John’s birth, they made a pilgrimage to the Church of Notre-Dame de la Recouvrance, about 120 miles from Ri, to dedicate their son to God. Their devotion paid off, as John developed a strong Catholic faith from a young age. A story recounts that when a playmate struck ten-year-old John on the cheek, John immediately fell on his knees, turning the other cheek in obedience to the Gospel command.

After being educated by a holy priest, John made his First Communion and received Confirmation around the age of twelve. It is said that he appeared like an angel in divine ecstasy on that day. Overjoyed, he soon after made a personal vow of chastity, dedicating his life to God, just as his parents had done for him upon his birth.

As a teenager, John was sent to the larger city of Caen, about thirty miles to the north, where he was educated by the Jesuits. The Jesuits, a new and respected order, were known for their excellent teaching. In Caen, John completed his philosophical studies and deepened his devotion, particularly toward the Holy Eucharist and the Blessed Virgin Mary. His devotion was so profound that his peers referred to him as “the devout Eudes.” After completing his philosophical studies, John’s father wanted him to return home and settle down. However, John explained that he had dedicated his life to God and pleaded to be allowed to continue his studies. His father relented, and John returned to Caen for theological studies under the Jesuits. After completing his studies, John joined the French Oratory of Pierre de Bérulle in Paris and was ordained a priest one year later at the age of twenty-four.

The French Oratory, distinct from the Roman Oratory of Saint Philip Neri, was founded in 1611 by Cardinal Pierre de Bérulle. Given the religious wars that had ravaged France in the late sixteenth century, Cardinal Bérulle took a new approach to Calvinism, fighting not with weapons, but with sound reasoning and faith. He is recognized as one of the founders of the French School of Spirituality, a Catholic Counter-Reformation movement that fostered personal devotion. This movement, emphasizing the Incarnation and the deeply personal nature of God, shifted away from the heavy focus on doctrine common in scholasticism. Instead, it fostered an intimate devotion through love of God and personal conversion. This movement greatly appealed to Father John Eudes, and he became a strong follower and leader within it.

After his ordination in 1625, Father Eudes fell gravely ill and was bedridden for almost a year. Once he recovered, he was sent to Aubervilliers, just outside Paris, for further theological studies. In 1627, his father informed him of a plague that had broken out in a village near his hometown. Father Eudes quickly ministered to the physical and spiritual needs of the victims, particularly encouraging them to turn to their loving mother in Heaven and to rely upon her intercession. When another nearby town experienced the same plague a few years later, he did the same. This time, out of fear that he would become infected and in turn infect others in the Oratory, he lived for a time in a barrel in an open field while ministering to the sick, unconcerned for his own well-being.

In 1633, Father Eudes began earnest preaching. He preached parish missions that would sometimes last for weeks or even longer. His sermons emphasized the mercy of God, and he rallied a large number of priests to hear confessions. He himself was an effective confessor who embodied the Heart of Christ to sinners. One parish after another was gradually transformed. During his missions, he developed a deep compassion for sinners trapped in cycles of sin, particularly prostitutes. To address their needs, he founded the Order of Our Lady of Charity of the Refuge in 1641, with the assistance of three Visitation sisters. The purpose of this order was to provide spiritual and material aid to repentant prostitutes who needed help to change their ways.

After ten years of preaching missions, Father Eudes began to notice that although people initially changed after a mission, they quickly fell back into their sins without ongoing spiritual support and guidance. To remedy this, Father Eudes turned his attention to the formation of the clergy. He realized he couldn’t single-handedly evangelize and offer ongoing spiritual support to everyone, and so, in 1643, he left the Oratory and founded the Society of Jesus and Mary, later known as the Eudists. The aim of this new congregation was to provide for the formation of seminarians and parish missions. Over the next thirty years, Father Eudes founded six major seminaries in France at Caen, Coutances, Lisieux, Rouen, Évreux, and Rennes. These seminaries not only formed seminarians but also welcomed priests for further education, formation, and retreats, and offered teachings to the laity.

Devotion was at the heart of Father Eudes’ ministry, and his most enduring legacies are his promotion of devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus and the Holy Heart of Mary. In 1648, with the permission of the local bishop, he instituted a feast in honor of the Holy Heart of Mary, fostering a realization of the love that the Blessed Mother had for her Son and for all people. Father Eudes later composed a Mass and Office in honor of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, which he celebrated with the bishop’s permission for the first time in 1670. His goal was to reveal the infinite and personal love of Christ Jesus for His people. Providentially, in 1673, a French nun and mystic, later to be a saint, named Sister Margaret Mary Alacoque began to have visions of Jesus, in which He conveyed the importance of devotion to His Sacred Heart. Among His requests, Jesus told her that He wanted the Feast of His Sacred Heart to be celebrated on the Friday after the octave of Corpus Christi, in reparation for the ingratitude of people for His Sacrifice. Thus, what Father Eudes was inspired to do in 1670, Jesus confirmed through a mystic shortly afterward. In 1856, Pope Pius IX extended this Feast to the Universal Church.

Saint John Eudes emerged as one of many saints within the Church in France during a time of spiritual renewal, using the weapons of personal devotion, prayer, adoration, frequent Communion, and Confession. Hearts were transformed, not just minds. To ensure that this renewal would be ongoing, he dedicated himself and his newly founded order to the formation of priests, providing good shepherds who emulated the Heart of Jesus to God’s people. As we honor this great saint, ponder all he did but especially his devotion to the Hearts of Mary and Jesus. Their hearts reveal who they are, along with their compassion and unbounded love for us all. Run to their hearts today and always, receiving from them all that you need for your own transformation. Then dispense the infinite mercy of God to others.

Source: https://mycatholic.life/saints/saints-of-the-liturgical-year/august-19—saint-john-eudes-priest/

Saint John Eudes, Priest Read More »